Conservation in Action: Plastic Architect’s Plans

Background and current state

In September 2021, a reader brought to our attention several plans which they did not wish to handle as the plans were very fragile and severely cracked. The plans were carefully removed from the folder and placed on some large sheets of polyester so that they could be transported to Conservation. Tim Warrender got to work and found that the plastic was a cellulose acetate drafting film – he continues the story of their treatment here.

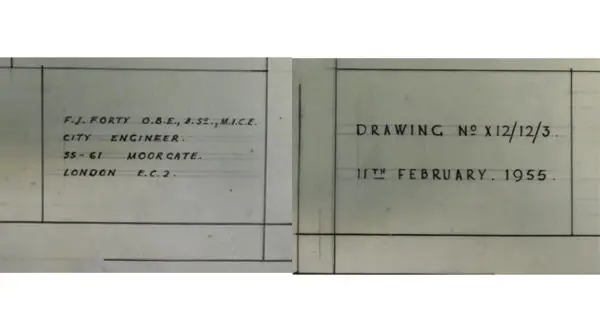

It was immediately obvious that these plans were plastic, but beyond that we had no knowledge of which plastic it was, or how to treat them. From research, I found that the plastic was a drafting film – until the mid 1950s the most used plastic was cellulose acetate, before polyester or polyethylene terephthalate took over. As the plans were dated 1952 to 1955, it was deduced that they were cellulose acetate as polyester / PET would not have decayed. Most of the plans had the name of the same City Engineer, F J Forty, on them.

A point to note is that drafting plans are referred to as ‘cellulose acetate’, but this term has been widely used to cover cellulose acetate, diacetate and triacetate, and it is not clear which of these is the material used.

Drafting films were used by the architect to make the original drawings. A plastic base was more dimensionally stable than paper or drafting cloth which had previously been used. After the plans had been drawn, they would then be photomechanically reproduced in blueprint form or other similar methods. The rear of the sheet was in its natural shiny state, but the front was treated with a rough finish so that the ink would adhere.

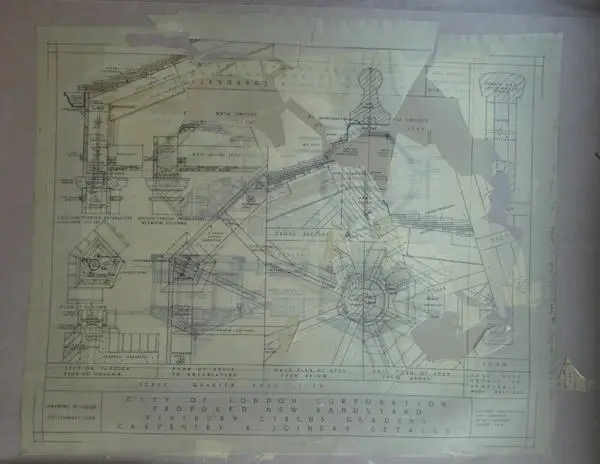

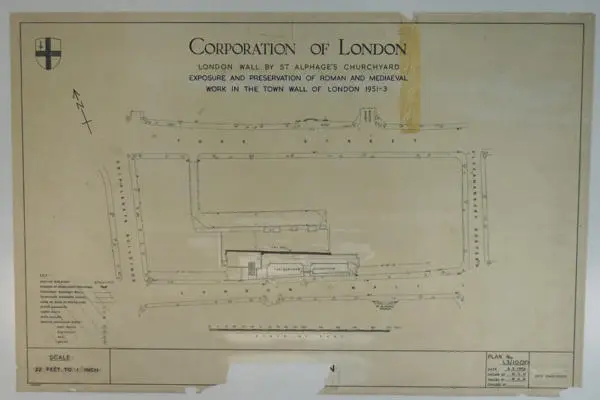

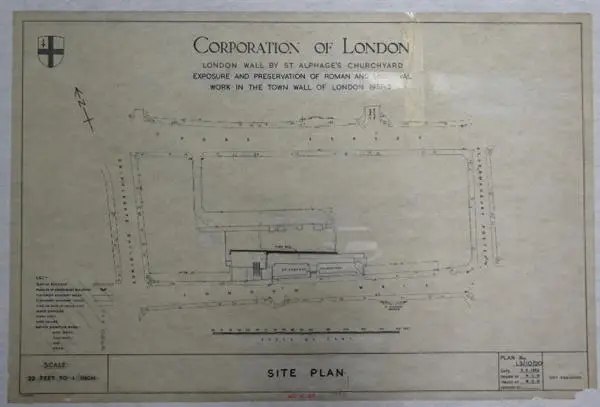

On closer inspection of our plans, I could see that certain parts of the plan had been printed on the back, namely the outer borders, ‘Corporation of London’, the City crest and some of the text at the bottom. Everything else had been written or drawn on the front, and there were some areas where alterations to the drawing meant that there were now shiny patches on the front as the original lines had been scraped off.

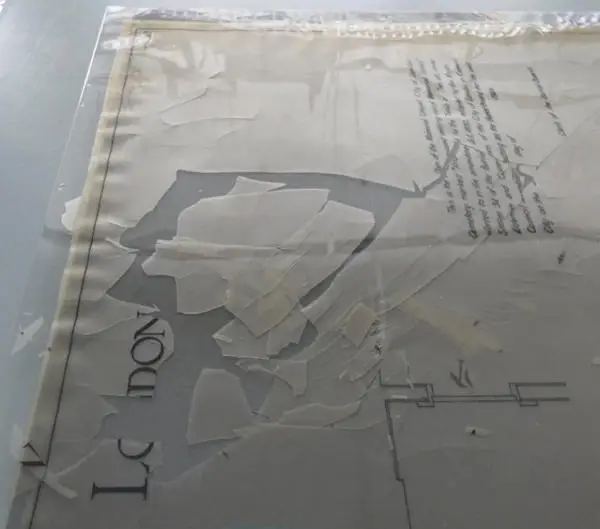

Along with the many cracks on the plans, some had also been repaired with adhesive tape, which had now discoloured and mostly dried out. The worst-affected plan was one which had already been enclosed in a polyester sleeve, and by the look of the damage most of this must have occurred since it was put in the sleeve. It is possible that the sleeve has created a microclimate which could speed up degradation.

The degradation is not the same as in cellulose acetate negatives, as there was no vinegar smell or crystalline deposits, so it looks likely that the cracking was due to the loss of plasticiser in the plans. The only discernible smell was that of the photomechanical plans which had been kept in the same folder.

Treatment

Whilst articles were available describing how to treat cellulose acetate negatives, or the previous use of cellulose acetate as a laminating film, I could find no reference to plans being treated. Therefore, I had to work out which methods to rule out before commencing the treatment. As the sheets are plastic, wheat starch paste may not stick sufficiently. Any adhesive that needed heat to set it was also ruled out as this would deform the plastic. Solvent activated adhesives such as Plextol or Lascaux were also considered, but for both of these the solvent most recommended to use is Acetone, and this would have reacted with the plans.

Knowing that gelatine has been used in photographic Conservation, I decided to try using some remoistenable tissue – tosa tengujo coated with gelatine. This was applied with a 50/50 mix of water and IMS (Industrial Methylated Spirit). I found that less of the liquid was needed as the plastic did not absorb it, unlike paper or parchment where I had previously used it. The outcome was very good, so I continued using this for the rest of the plans. For the most part this was only used on those areas which were already cracked, but for two of the plans with the worst damage, the whole plan was backed with the coated tissue.

Of course, before any of the repairs could take place, I also had to remove the adhesive tape residue. For the areas where the adhesive had dried out, the residue was carefully scraped off. Where the adhesive was still tacky, I used a crepe rubber to pick up the adhesive. The removal of the tape not only made the application of the new repair more effective, but it also removed the visually distracting brown from the plans.

When the plans were fully repaired, they were put in a new sleeve, with clear polyester at the front, and bondina, a non-woven white polyester, at the back. The bondina was used as it is breathable, and so does not lock in any gases given off by further degradation. It also has the benefit of giving a white background which ‘hides’ the repair tissue, making the plans more readable.

The enclosed plans were finally put into folders which had extra strengtheners so that any future damage to the plans would be minimised.

Footnote

Cellulose acetate is now being branded as a green plastic as it derives from wood / cotton origins rather than being petroleum based, and will easily biodegrade when put in landfill.

References

Transparent Drafting Films: Profiles for Preservation (culturalheritage.org)