Celebrating Grinling Gibbons in the LMA collections

300 years of a master craftsman

The carving work of Grinling Gibbons adorns the churches, historic houses and Royal residences of London and beyond but is perhaps a name not as widely known as his contemporary Christopher Wren. Gibbons has been described as the Michelangelo of woodcarving. Charlotte Hopkins looks at his life and how it is celebrated in the LMA collections.

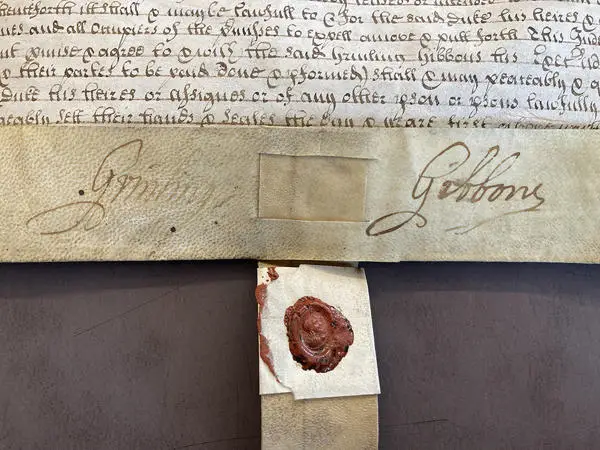

Gibbons was born in 1648 and brought up in the Netherlands in Rotterdam after his father who was a draper had travelled there as a merchant. Gibbons later became a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Drapers in 1672.

He was likely influenced by the tradition in Northern Europe to represent the natural textures of the medium of wood in a realistic manner. Limewood was lighter and easier to manipulate than the traditional medium of oak and therefore the delicate details of flowers, for which he had a passion, could be gracefully reproduced. The flamboyant flourishes that Gibbons so expertly carved were a pinnacle of the freedom of design expressed in Baroque-era design.

Deptford

Gibbons left the Netherlands for England when he was nineteen. He first lived in York before moving to Deptford in South East London to work as a carver for the local shipbuilding industry. He was discovered here in 1671 by the diarist, John Evelyn, who saw him through the window in his small thatched cottage carving a version of the ‘Crucifixion’ after Jacopo Tintoretto. This is now in the care of the National Trust at Dunham Massey, Cheshire. Evelyn wrote in his diary that the work of Gibbons was “equal to anything of the Antients”. Through Evelyn he was introduced to Wren and King Charles II.

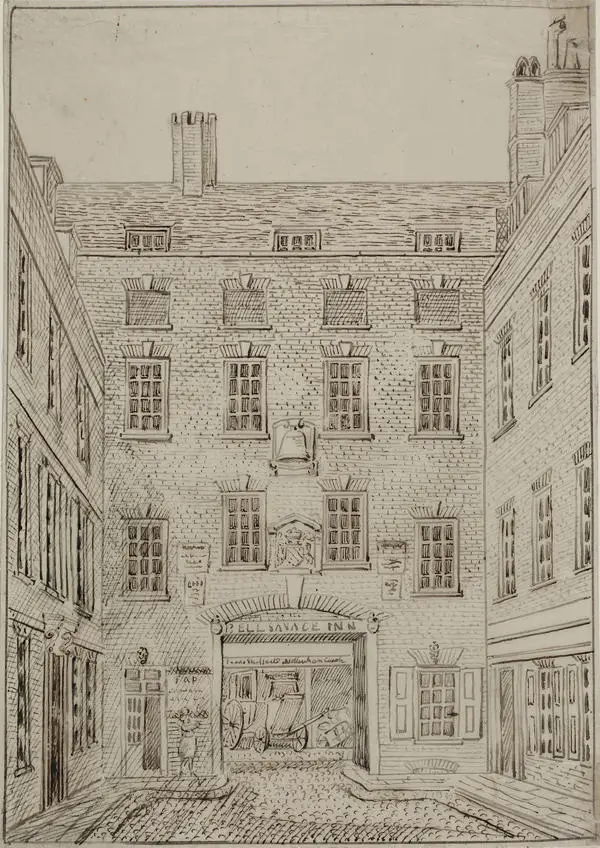

Ludgate Hill

Around 1671 to c.1678 Gibbons was living in the City of London at the Belle Sauvage, Ludgate Hill with his wife Elizabeth. The family were then established at Bow Street where he died in 1721 and was buried at St Paul’s, Covent Garden with no monument at the time of his death.

"Immediately south of the Earl's houses two others (Nos. 29 and 30) were put up on sites that were no longer part of his estate… In 1702, one of these houses, which was at that time inhabited by Grinling Gibbons, fell down. Gibbons thereupon moved to an adjacent site southward, and built himself a new house under a lease from the first Duke of Bedford."

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol36/pp185-192#p11Survey of London

St Paul’s Cathedral

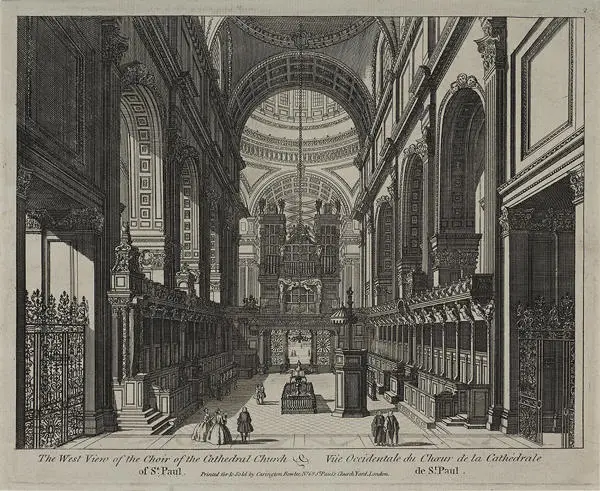

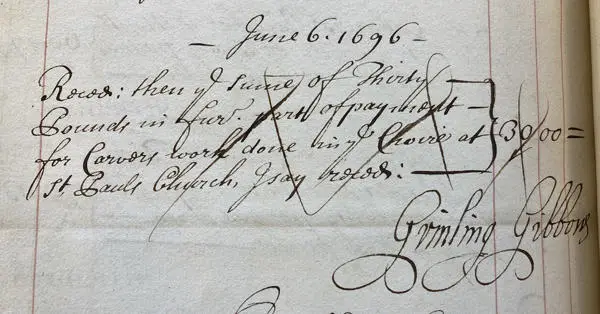

After the Great Fire, Wren embarked on planning and re-designing the new St Paul’s Cathedral in the English Baroque style. In 1675, Gibbons was just starting out on his career when he got the job of undertaking carving work in the Cathedral. The Choir was one of his major achievements as can be observed in this print from c.1750.

"The two rows themselves are modestly adorned with oak carving. Behind them are boxes and closets and above these, a limewood frieze of fruit and flowers, broken by the cherub caryatids which support the overhanging gallery. Each section of the frieze is different, and so, too are the beautiful oak cherubs which lean forward from acanthus sheaths round their hips. Above, on the gallery, is a second frieze. Here limewood cherubs with crossed wings shelter beneath projections of the cornice, separated by wave-like ‘leatherwork’ scrolls carved from oak. From the scrolls hang floral garlands in limewood. The effect is rhythmic and balanced, and the regularity of design serves to emphasize the three special stalls which rise above the rest of the Choir."

London Transport Guide to Grinling Gibbons (Baynard Press, London 1971)

Gibbons’ speciality was carving natural forms and delicate features of fruit, flowers, birds, leaves and petals, ropes and garlands. The Cherubs were thought to have been carved in the likeness of his own children. Preparatory drawings were made, and a pattern was traced onto a block to cut out the design, building up the layers which were often stuck together to create the three-dimensional effect.

"Gibbons would have had hundreds of tools, including many different gouges and chisels. Modern carvers still use tools called ‘Gibbons’, possibly invented by him. In working Gibbons first made preliminary sketches – some of which have survived – and probably copied the main lines on to the surface of the wood. Modern carvers sometimes make use of clay models to see how relief will stand out and shadows fall."

London Transport Guide to Grinling Gibbons (Baynard Press, London 1971)

London Picture Archive

Other examples of Gibbons’ work can be explored on the London Picture Archive. Look out for the font at St James’ Piccadilly (LPA: 21797) , the oak board room in the New River Head building on Rosebery Avenue (LPA: 329295) and also works in bronze such as the statue of James II outside the National Gallery ( LPA: 29693) and the statue of Charles II outside the Royal Hospital, Chelsea (LPA: 224594).

Out of fashion

As fashions changed Gibbons’ work suffered from neglect as a plainer style with less embellishments was favoured. The Victorians took a dislike to the Baroque period and in the 1870s removed his grand organ case at St Paul’s Cathedral splitting it into two and placing against the pillars either side of the choir. Other examples of his work were ravaged by fire at Hampton Court and required the skilful craftsmanship of restorers to recreate its former glory. The V&A had a major exhibition in 1998 covering his work and it is perhaps time to admire his beloved acanthus scrolls once again.

Resources

In the LMA library:

- London Transport Guide to Grinling Gibbons (Baynard Press, London 1971) 45.09 GIB

- St Paul’s: the cathedral church of London 604-2004, edited by Derek Keene, Arthur Burns, Andrew Saint. 56.0 KEE

Online:

- Master Carvers’ Association

- V&A publication - Grinling Gibbons and the art of Carving