Foundling Hospital - the health of London children

From Coram’s Foundling Hospital archives

The health of London children under institutional care, 1890-1916

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a large number of children in London were in institutional care. Poor Law schools cared for children whose parents were in the workhouse or who had been maltreated by their parents. The Foundling Hospital cared for illegitimate children given up by their mothers from a very young age. The training ship Exmouth cared for boys who were training to join the Navy or merchant marine. Over time these institutions became more and more interested in the welfare of the children they cared for and collected vast quantities of information about the children’s health and welfare.

In this article, Dr Eric Schneider of the London School of Economics and Political Science analyses some of this evidence, melding historical analysis of sources with the statistical and analytical tools of modern epidemiology to begin to answer three questions: how healthy were children in turn of the century London; what were health conditions like in children’s institutions; and how did institutional care affect children’s health?

How do we know about child health in institutions?

Before answering these questions, it is first important to give a brief description of the sources used. Most of the findings in this article come from the records of two institutions, both held by London Metropolitan Archives.

The first institution is Ashford School in the West London School District. This was a Poor Law school founded in 1868 as a collaboration between five Poor Law unions in west London, located outside London in a semi-rural setting. The school housed orphans, deserted children, illegitimate children and children whose parents were in the workhouse. This article focuses on the history of this institution from 1908 to 1916 and draws upon the Medical Officer’s report book, the signed minutes of the Board of Management, and papers about diet and related matters These sources contain detailed quantitative and qualitative information about the children’s health.

The second institution is the Foundling Hospital. Founded in 1739, it had cared for over 25,000 children by the time it stopped boarding children in 1955. The hospital accepted illegitimate children of respectable mothers in infancy. The children were then placed with foster mothers in the countryside in Kent or Surrey until the age of five or six before returning to the central London site until they were 15 or 16. The research in this article is drawn primarily from the meticulous record of individual children’s health kept by the hospital’s Medical Officer from 1892 to 1914 found within Coram’s Foundling Hospital archive at LMA. It contains information about each child’s height and weight at various ages and whether or not they died.

These two sources provide a wealth of detail about the health of children in institutional care.

How healthy were children?

Historians have long used child and adult height as a proxy for the health of children. This is because child growth is very sensitive to environmental conditions such as the nutritional quality of the diet and exposure to diseases such as diarrhoea and respiratory illness. Thus, the height of children can be used as a proxy for the health environment that the children had experienced up to that point in their development. In fact, the percentage of children who are too short for their age (the stunting rate) is used as an indicator of malnutrition in developing countries today.

Institutions in late nineteenth and early twentieth century London were also interested in the heights and weights of children in their care, and many institutions measured the height of children upon admission. Some also recorded multiple height and weight measurements of children usually at admission and discharge from the institution allowing us to observe how children grew as they aged.

If we compare children in London institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century to normal school children at the same age in the same time period, we can see that the children in Poor Law schools were shorter. The average ten year old school child in London in 1905 was around 130cm tall, but children in the Ashford School of the West London School District in the early twentieth century were approximately 123cm tall. This 7cm difference in height suggests that the children in Poor Law schools came from very deprived backgrounds, even for their day. However, even the average London ten year old in 1905 was substantially shorter than we would expect from a ten year old today. The average ten year old child now would be approximately 138cm tall indicative of the substantial increases in child health over the past century.

What were health conditions like in children’s institutions?

Victorian children’s institutions normally conjure up the horrific scenes described by Dickens of children eating gruel and living near starvation. However, by the turn of the twentieth century, children’s institutions had become increasingly concerned about the health and wellbeing of their charges. As mentioned above, this led institutions to collect information about the children’s health and improve living conditions.

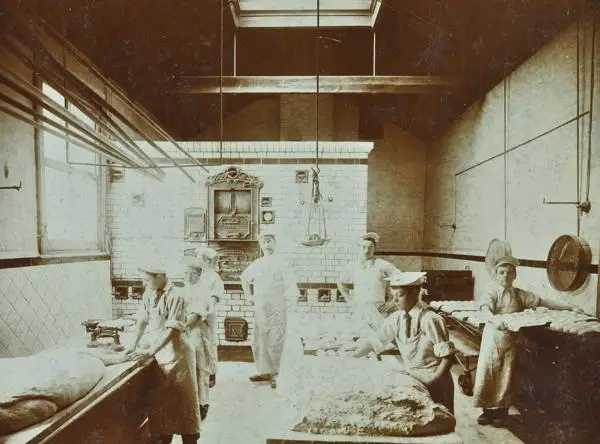

Institutions improved their care provision in three main ways. First, they enhanced the quality and variety of the diet that the children received. LMA holds a great number of menus and recipes used by Poor Law schools from the 1880s to 1920s, which allow us to understand how these conditions changed. Although the total quantity of calories may not have increased all that much, as time passed, children were given larger quantities of milk, meat, fruit and vegetables that surely improved their health by providing the vitamins and minerals they needed. By the 1910s, the West London School District also had a complex system of checking the quality of the food they purchased. They boiled the milk and checked it for contamination, only accepted certain cuts of meat from trusted vendors, and reported when vendors supplied low quality flour, raisins and cocoa.

Institutions were also concerned about sanitary conditions and made progress in improving hygiene as well. Again, there is rich detail for the West London School District. In the early twentieth century, most of the toilet facilities were earth closets where excrement was kept in a closed container that had to be emptied regularly. However, between 1909 and 1911, the school connected to a sewage system and installed water closets, which could more efficiently dispose of waste. The school also monitored the water supply drawn from a deep well, testing regularly for signs of impurity. The children bathed only once a week, but washed their hands with soap using primitive sinks and running water. Interestingly, there were no reported cases of typhoid in the West London School District 1908-17 or in the Foundling Hospital 1897-1915, which suggests the institutions had excellent processes in place to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases.

Finally, institutions worked to prevent the spread of illness by quarantining sick children in an infirmary and keeping newly admitted children apart from the general population until they were proved to be healthy. Both the West London School District and the Foundling Hospital operated infirmaries where sick children were cared for until they overcame their illness. The infirmaries were run by a medical officer and a team of nurses who looked after the children and ensured their return to health. The Foundling Hospital had the same Medical Officer, W. J. Cropley Swift, from at least 1892 to 1917, so these medical officers were very important for maintaining the health of the children. The Foundling Hospital also paid Medical Officers to visit the children placed out of the institution in Kent and Surrey during their first five years to ensure that foster mothers were taking good care of them and to treat the children for any illnesses.

This paints a relatively rosy picture of the health conditions of children in institutions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. However, it is useful to test these qualitative descriptions with some hard numbers using methods from modern epidemiology.

How did institutional care affect children’s health?

We can test whether the experience of children was better in institutions than outside using two methods: we can track their growth while in the institutions; and we can compare mortality rates for children inside and outside of institutions to see if deaths were more common in the institutions.

As mentioned above, the children entering Poor Law schools were shorter than both modern children and the average child in London in 1905, indicating that they were deprived and unhealthy. However, in order to understand how institutional care affected their health, we can track their growth between admission to the institution and discharge from the institution to see whether they moved closer to the healthy standards of today. This growth is known as catch-up growth because children catch-up to their healthy peers when their nutrition and general health improves.

If we look at children admitted to the West London School District, boys and girls grew 0.6 and 1.4 cm more respectively than we would have expected them to grow during their time in the institution. Boys and girls also gained 1.1 and 0.8 kg of weight more respectively than we would have expected. This suggests that the suite of health interventions described in the previous section provided a better health environment for the children than they had faced before entering the institution. The West London School District substantially improved the children’s health.

An analysis of the weights of children who were admitted to the Foundling Hospital provides a similar story. The average infant born in the Foundling Hospital gained 2.3 kg more than would be expected by the time they reached the age of 5. Although foundlings were boarded out in rural Kent and Surrey across these ages, their weight gain still shows that the Foundling Hospital was able to improve their health conditions relative to the time before they entered the hospital.

A second way to understand whether children living in institutions received better care than their counterparts living in the rest of London is to compare mortality rates of children in institutions to those living outside. On this count, the institutions again seemed to do fairly well. The comparisons are easiest to make for the Foundling Hospital. Infants under Foundling Hospital care had higher mortality rates than London in the first four months, but infant mortality risk fell as the children aged reaching rural levels by the end of the first year.

Early childhood mortality, deaths to children aged 1-5, presents an even better picture. The early childhood mortality rate in the Foundling Hospital was 3.7 deaths per thousand children. This rate was lower than the comparable rate in London (9.4 deaths per thousand) and also lower than the rates in Surrey and Kent where the foundling children were fostered until age five or six (5.4 and 5.8 deaths per thousand respectively). Thus, it seems that the Foundling Hospital provided better nutrition and medical care than was available to the average child at the time.

Concluding thoughts

Children entering Poor Law schools and the Foundling Hospital experienced real deprivation before entering the institutions. However, once in the institutions, many children’s health improved. They experienced catch-up growth and had a lower risk of dying than the average child in the surrounding area. These institutions provided better care than children received from their families because they provided greater quantities of and higher quality food. They also provided a standard of medical care that was far above the normal standard of the time.

Archive sources at LMA

- West London School District

- Signed minutes of the board of management, 1907-21 (WLSD/024-029)

- Dietary tables, recipes, etc., 1892-1926 (WLSD/468)

- Medical Officer’s report book, 1906-17 (WLSD/435)

- Coram’s Foundling Hospital archive

- Medical record, 1893-1938 (A/FH/A/18/015/001 – access by permission only)

Further Reading

- Schneider, Eric B., 2016. Health, Gender and the Household: Children’s Growth in the Marcella Street Home, Boston, MA, and the Ashford School, London, UK. Research in Economic History, 32, pp. 277–361

- Arthi, Vellore & Schneider, Eric B., 2017. Infant Feeding and Cohort Health: Evidence from the London Foundling Hospital. CEPR Discussion Paper, pp. 1–83.

- Schneider, Eric B., 2021. The effect of nutritional status on historical infectious disease morbidity: evidence from the London Foundling Hospital, 1892-1919. Economic History Working Papers (328). Department of Economic History, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

About the author

Dr Eric Schneider is an Associate Professor in the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics and Political Science conducting research in the history of health and historical economic demography.

The Foundling Hospital archive is owned by the charity Coram, undertaking pioneering work in adoption, early years and parenting from the original London site of the Foundling Hospital. You can explore the history of the Foundling Hospital further and even volunteer for an online project to transcribe its archives through the Coram Story website.