Garden Museum loan

Collection background

John Alfred Groom was a London engraver and evangelical preacher, who became concerned with the plight of the poverty-stricken and often disabled girls and women who sold flowers and watercress in the streets around Farringdon Market. His work with them began when he founded the Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission in 1866.

Taking inspiration from the trend for imported handmade flowers, John Groom set up a factory in Sekforde Street, Clerkenwell, close to the Woodbridge Chapel, where disabled girls could work at making artificial flowers and thus make a living for themselves. The girls lived in houses in Sekforde Street, rented by John Groom. Further factories were subsequently built in Woodbridge Street and Haywards Place. The name of the charity was changed to John Groom's Crippleage and Flower Girls Mission in 1907, and moved to Edgware in the 1930s.

The pattern book

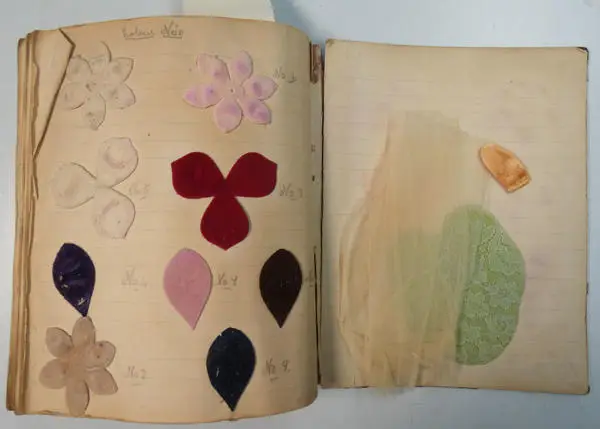

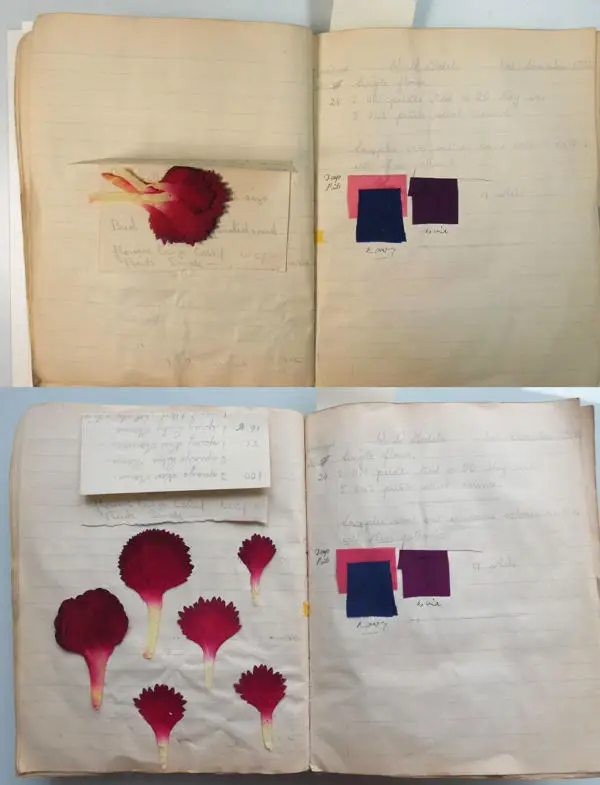

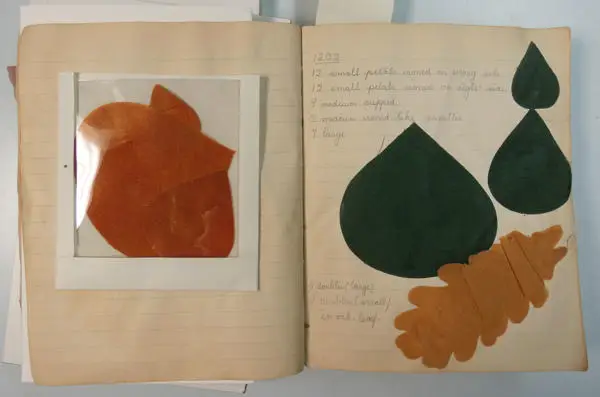

The pattern book (reference: LMA/4305/04/015) contains samples of the parts which were put together to make the flowers, and occasionally a complete flower. These pieces are usually some form of textile, with some paper templates. Alongside these samples are descriptions of how many petals, leaves etc make up the flower. A couple of the pages are dated December 1937.

The Garden Museum had requested to borrow this book as part of their exhibition 'Wild & Cultivated: Fashioning the Rose', which meant that treatment needed to be carried out to affix the loose items to the pages. From previous experience of working with textiles, a remoistenable tissue coated with Lascaux adhesive, was used.

Whist this worked for most of the textiles, a small amount had their challenges. Some of the dyes in the textiles, especially in the red flowers, were not fixed. This meant that extra care was needed when re-activating the adhesive on the tissue. The other issue was that remoistenable tissue would not stick to some of the textiles used. For these examples, a paper pocket was made and attached to the page, and the petals were put into a polyester sleeve which slotted into the pocket.

At the same time as the re-attachment, it was decided that we should flatten some of the samples which had been accidentally folded over. This was done by using a thin line of water, and then pressing under a weight. The samples with the fugitive dyes were avoided.

We decided not to work on the binding even though there were issues with the spine, as it would be easier to display as it was without the threat of making things worse.

When we received the book back at the end of the exhibition, we were pleased to find that all of the petals were still attached.