Julius Caesar Taylor's Molly House - Tottenham Court Road

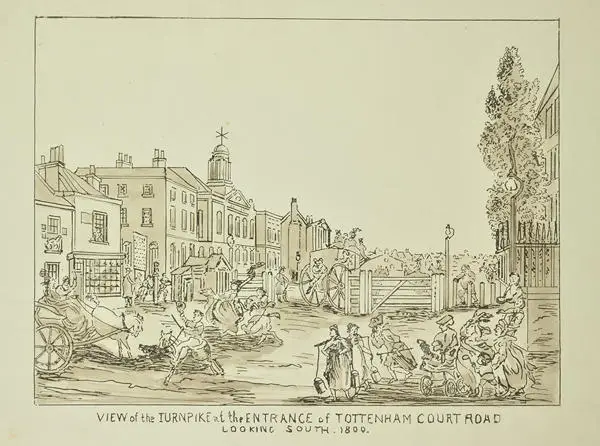

Tottenham Court Road today lies at the centre of London’s bustling shopping and theatre experience but 300 years ago this was much a humbler road and home to a key location in the capital’s LGBTQ+ history. During the 1720s you would find a molly house was run by Julius Caesar Taylor. Despite being punishable by a fine, imprisonment, or even death, private social spaces existed in London where gay men from all classes could meet safely. Establishments called ‘Molly Houses’ dominated, ranging from private back rooms in gin shops to three storey public houses run by male couples.

The term ‘gay’ is used here to reflect the dominating visibility of men who sought relationships with other men. The names, labels and communities who reflect this sexuality has changed over time and will not reflect exactly those of today. In the 1700s a very well organised ‘molly’ subculture existed. Early figures in the Church branded men who had relationships with men as molles or sissies, with wider society labelling effeminate men molly-coddles and mollies. Having no other term except the Biblical or legal ‘Sodomite’ or ‘Bugger’, gay men transformed ‘molly’ into a positive term of self-identification, in the same way that derogatory queer has been reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ community.

As with many Molly Houses, Julius Caesar Taylor held initiation rituals for visitors that included being given a female name and having a glass of gin thrown in your face. The females names they were ‘christened’ with were called ‘Maiden names’ and there are several examples from criminal trails: Primrose Mary (a butcher in Butchers Row); Orange Deb (Martin Macintosh, an orange seller); Nurse Mitchell (a barber); and Miss Sweet Lips (a country grocer). Flying Horse Moll frequented Julius Caesar Taylor’s House and obviously knew London’s LGBTQ+ scene well, having been previously arrested during a raid on New Year’s Eve drag party at a house near Drury Lane. Moll and thirty-nine other men, some of them dressed as queens and shepherdesses, fought with police officers before being taken before the Justices of the Peace still dressed in their costumes.

A description from the journalist Ned Ward in his book ‘The Secret History of London Clubs’ published in 1709 described that the men referred to each other as sisters and using female pronouns. The mollies had ‘children, sisters and husbands’. Through this they created their own family networks, adding to the long tradition of LGBTQ+ people creating a chosen family that is more accepting and open about identity and sexuality.

As well as being the owner of a Molly House, Taylor was clearly part of this gay subculture as he was arrested in 1728 and found guilty of having “indecent relations with another man”, John Burgess. At the trail it was said that Taylor “was seen to sit on the Lap of John Burgess, when they committed such indecent and effeminate Actions, as are not to be mentioned”. Importantly John Burgess, Taylor’s lover, was also charged for assaulting Taylor, so while seemingly a consensual relationship, in the eyes of the law their actions were deemed criminal. Alongside this conviction, Taylor was accused of "keeping a disorderly House, and entertaining wicked abandon'd Men, who commit sodomitical Practices". He was fined ten Marks and five Noble, while John Burgess was fined five Marks.

Julius Caesar Taylor was likely a previously enslaved Black man, for this kind of classical name was commonly given to enslaved people taken from the Caribbean by British enslavers. By the mid-18th century, Britain had a growing African and Caribbean population with London becoming a central hub. Sadly, little information survives about the individual men, women and children brought to England. However, several previously enslaved people gained prominence in British society. Ignatius Sancho (1729–1780) became a central figure in the abolitionist movement, even gaining status as a male property-owner. This meant he could legally vote, becoming the first known Black Briton to have voted in Britain. He was famous for his poetry and music, and his friends included the novelist Laurence Sterne, David Garrick the actor and the Duke and Duchess of Montague. Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745 – 1797) and Ottobah Cugoano (c. 1757 – after 1791) were equally well-known, and active in campaigning to abolish slavery.

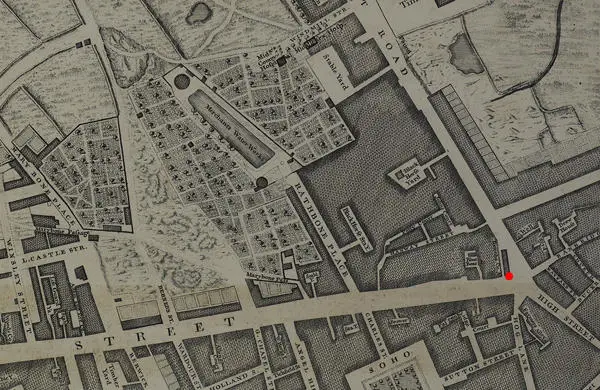

![Parish Register for All Hallows Church in Tottenham, North London including a reference to “Julius Cesar a Black was Buried on Sunday August y [the] 19th 1733"](/image-library/Images/Things-to-do/lma-julius-cesar-register.x8c6cff04.jpg?q=70&f=webp&w=600)

Evidence we do have of Black, Asian and Indigenous Britons comes from church records, with many being baptised and marrying White Britons, which was illegal in colonised countries but not in mainland Britain. The above image is from a Parish Register for All Hallows Church in Tottenham, North London and is possibly a report of Julius Cesar Taylors burial, pointing out he was Black. This is less than five years after his arrest. Although we cannot confirm this was him, it gives a picture of what could have become of him.

You can discover more stories of Black, Asian and Indigenous Britons through the 'Switching the Lens project - Rediscovering Londoners of African, Caribbean, Asian and Indigenous Heritage, 1561 to 1840’.