Pungent!

Reading The Scent of the Archive by Caroline de Stefani has set Jeremy Smith thinking more about smell from a slightly different angle. Caroline describes this archivally neglected sensory experience in terms of archival materials and considers the diagnostic information available to conservators. But what about smells that are directly related to the document sources? Might smell have a role beyond the conservation studio? Jeremy sniffs out some possible leads.

We know that a lingering aroma might be suggestive of the ownership or storage of an item. Caroline mentions cigarette smoke and church incense, but surely more exciting for the researcher would be a collection with a smell redolent of the actual circumstances of its creation. Can we hope in coming months to receive an archive of Covid Risk Assessments smelling faintly of alcohol hand sanitiser?

Several academic projects, including the smell heritage group within UCL Dept of Sustainable Heritage and 'Odeuropa' based in the Netherlands are forging new research in this area. They aim to kick back from the position that 'our knowledge of the past is odourless' and encourage the preservation of distinctive smells that might tellingly illuminate an event or represent the emotions of a moment in time. So where might we look in the collections of LMA for olfactory traces of the former life of documents?

London itself is of course our prime document. Cities are continuously losing old scents and gaining new ones. Those of us old enough to have wandered amidst the empty brick warehouses of Thames side London, while they were still caught in that bubble of time between working use and re-emergence as luxury dwellings, will never forget the astonishing wafts of spice aromas emanating from the wooden joists within these cavernous spaces. Smell memory is not reliable, but I would make the case for a dominant strain of cinnamon.

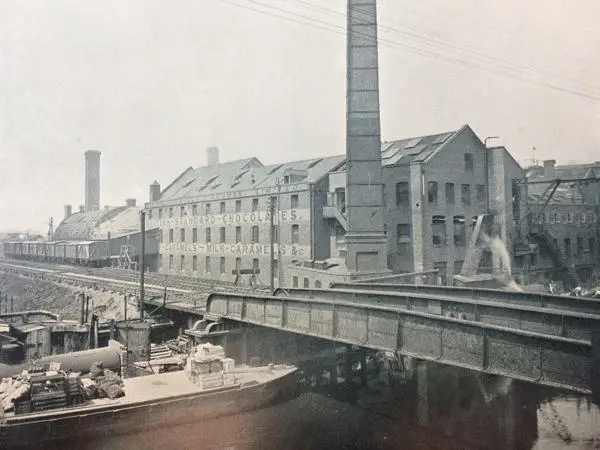

Commuters into London Bridge may remember (if they also remember train windows which could open) being informed of imminent arrival at London Bridge Station not by the train announcements but by the heady smell of freshly baking Custard Creams or Bourbon Biscuits (depending the day of the week). The vast Peek Freans biscuits factory stood adjacent to the tracks in Bermondsey.

But some of our archival collections suggest themselves as receptacles of the historical aroma of London. Might Gas company records, the Sewers collections or Lyons cakes archives have absorbed the smell of the environment in which they spent their active life?

Unfortunately, I have so far found no evidence of such delights. If only the records were hermetically sealed before arrival at the archive we might enjoy for example the jams and pickles of the Soho branch of Crosse and Blackwell (we have their Soho Square premises records including staff scrapbooks LMA/4467/E and labels LMA/4467/C or how about their subsidiary: British Vinegars LMA/4467/H).

My kitchen cupboards inform me that leaf tea aromas may linger quite stubbornly, but no such tang from J. Lyons caterers immense bagging and packaging activities has been detected in the J. Lyons Archive (ACC/3527).

Saved from edge of the Olympics development site at Hackney Wick is a promising candidate. Confectioners ‘Clarnico’ (Clarke Nicholls and Coombs) manufactured sweets here from 1887 to 1972 and at the height of their very successful business were employing more than 2000 people. Clarnico achieved a worldwide reach with their famous products which included Peppermint Creams and Toasted Haddocks. Local people put on record the aroma of sugar which pervaded the streets and canals in this part of the borough, only occasionally displaced by the scents from the cough medicine factory and the fertilizer factory which were neighbours. Any lingering olfactory trace of the Clarnico liquorice department, the 'French Fancies' Department or the Lozenge Department would surely connect us more directly to the enthusiasm of the young sweet eaters than any text could.

Visual artists in the LMA graphic collections have for obvious reasons struggled with the representation of smell. Hogarth famously plays quite prominently with the sense of hearing, (note for example the Foundling Museum exhibition Hogarth and the Art of Noise, 2019) but he was far more hard-nosed about smell, going little further than the inclusion of an occasional jar of smelling salts. Even the many images of London’s famous street cries, which might indeed be hoped to contain some visual suggestion of the heady miasma surrounding such sellers as the 'cat’s meat' man or seller of 'cheap fish' (see London Picture Archive for a gallery of many street cries and traders) but these are well deodorised images with not so much as a wrinkled nose.

The Odeuropa project will conduct ‘sensory mining’ of texts. There would be much to be found at LMA, though the research will inevitably be based on digitised material. As early as 1708 Edward Hatton writing his ‘New View of London’ from a London bristling with coffee houses found great amusement in the St Dunstan’s West parish wardmote court minutes of 1657 where the 'evill smells' of the making (apparently by day and night) of 'a drink called coffee' is listed as one of the ‘disorders and annoyances’ to be dealt with by the parish (CLC/W/JB/044/MS03018/001).

Museums have for several decades made use of smell as a tool in presenting collections (such as to evoke Chaucer’s Canterbury or Viking York, for example) but there is growing interest in art galleries to suggest the smells that would have been experienced by artists as they worked. The Mauritshuis in The Hague for example provided small dispensers for visitors to the exhibition ‘Fleeting - Scents in Colour’ (and digital visitors) so that the smell of a floral cornucopia, or a stinking canal, or fashionable pomander necklaces could be experienced in front of the relevant artworks.

But at LMA it seems that short of discovering some hermetically sealed archives it is the whiff of paper degradation that our users and cataloguers will experience rather than anything more evocative.