Scattered homes

Lost childhoods in Camberwell, East Dulwich and Peckham

If you could write about anything that happened in the past, what would you choose? For some this might seem a daunting question, but for Nina Bea in 2016, when she started her MA in History with the Open University, it was what she looked forward to most. She knew that she wanted to study London in the Edwardian period, focusing on the socio-economic conditions of the poor. And she hoped that LMA would have some material related to a topic in which she was particularly interested: an experimental foster care concept for children called ‘scattered homes’. She was delighted to find a treasure trove of information and this is the story of her research and what it revealed about the children’s lives and those of their parents and the foster carers.

Scattered children’s homes were unlike cottage homes (such as those built in Barkingside by Barnardo in the 1870s). While cottage homes occupied one big site and were insular, scattered homes were ordinary suburban villas rented by poor law guardians to place about ten children ‘scattered’ out in the community with paid foster parents. The idea was that destitute children would blend in rather than stand out and be stigmatised. Most important to the guardians, they would not be spending time in the slums or Gordon Road Workhouse with their own poverty-stricken families.

A bit of digging around on the web had led me to seek out documents relating to the poor law union of Camberwell St Giles, South London. The historic parish of St Giles had covered Camberwell, Peckham and East Dulwich, an area I had once lived in. I initially went to LMA not expecting much, but on entering the search term ‘Camberwell’ into the electronic catalogue, my hopes lifted: it returned me 63.35 linear metres of records under the catalogue series for the poor law parish, CABG.

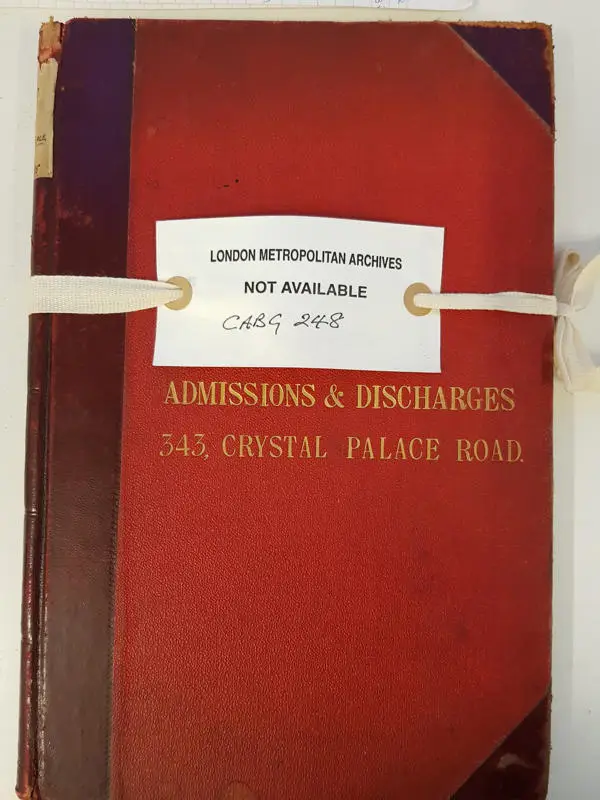

And what a treasure trove there was to be uncovered! As well as minutes of children’s committee meetings chronicling the time the homes were being set up (from 1897) (CABG/039-040, CABG/075), there were reams of records relating to apprentices (CABG/196), finances (CABG/096-098, CABG/212/007-009) and - crucially - registers relating to the individual houses rented in the scheme (CABG/239-270). Funnily enough I had lived opposite three of the houses in East Dulwich without ever realising their history as children’s homes.

A thorough read-through of minute books from the 1890s to the 1910s revealed to me what a huge operation had been put in place. By 1913, more than 600 children aged three to fifteen were being cared for simultaneously at 52 separate addresses across Peckham Rye and East Dulwich.

Early on, I came up against the issue of data protection. Most of the house registers were not accessible to the public. I had not realised that scattered homes existed up to the 1930s. Some of the registers begun in the early 1900s were still in use 30 years later - meaning that some children listed in them might still be alive. With confirmation of my project from the OU, LMA kindly agreed to open a selection of registers to me up to my project end date of 1914 and I agreed not to look at register entries beyond this date.

I whittled my project down to four specific houses (with additional background context gleaned from three others). This provided a unique window into the lives of 743 children who, with the exception of individual case studies gleaned from minutes and matched with newspaper reports, census entries, and other publicly available documents, was anonymised for the purpose of spotting trends across time and between the selected houses.

The scattered homes registers are so much more detailed than the census records for the same houses in 1901 and 1911. It was possible to see what dates children entered, who their nearest relatives were, and addresses where they might be found. Most children, contrary to popular myth, were not orphans. More than half had a mother still living, and fewer, but still in significant numbers, had both parents living. Often, the reason for children being in care boiled down to parental ill-health. With wages so low, if a father was struck down, the whole family was imperilled.

What was most revealing was how often the children left and returned. They might stay for two nights, a week, a month, or as long as three years, depending on their personal circumstances. Children were meant to see their birth families as little as possible and applications to visit them were often refused. But the registers show that parents regularly checked their children out of the system altogether for contact, returning them when it was clear they could not survive outside.

The same children’s names kept cropping up, first in one house, then another - with the minutes telling stories of absconded parents, child misbehaviour including stabbings, and chronic ill-health. Some children had no details - more than once a toddler was ‘brought in by police’ after being found wandering the streets. Siblings were often kept at different addresses and in care for different lengths of time. The registers highlight the sheer chaos of administering who came through the seemingly revolving doors.

The minutes of committee meetings added extra fascinating layers of detail, particularly the burden and strain that foster parents were under. They were largely lone foster mothers - an irony, given that many of the children’s own mothers were refused financial help to look after them single-handed. These foster carers, often working into their late sixties, were in charge of a minimum of ten children on a whole-time contract (effectively 24/7 with one Sunday in six off) for two pounds ten shillings a month, plus bed and board. This salary remained static from 1898 until at least 1913.

Many women injured themselves in the line of duty, fell ill with mental exhaustion and even died while in service. Others were punished for cutting corners (such as taking an evening off and leaving children locked indoors alone, or for meting out corporal punishment, which was forbidden for girls). The guardians’ minutes show they regularly had to recruit - it was clearly difficult to find women who would stay and who were mentally and physically strong enough to do the work.

As well as the wealth of poor law records, LMA was rich in supporting information that became invaluable, including rare textbooks and directories. Its bank of maps meant I was able to visually overlay the children’s homes onto the neighbourhood to see how they were scattered. As with many of Britain’s nineteenth century slums, vast swathes of Peckham have since been cleared and rebuilt. The LMA digital photo archive London Picture Archive allowed me to piece together what the children’s home neighbourhoods might have looked like.

For every child’s story I was able to tell in my dissertation, there were hundreds more examples I could not fit in. Those who ran away; those who were incarcerated in homes for delinquents; those whose mothers were in asylums; those whose parents had committed murder or suicide. They have all left an indelible mark on me. For that reason, I’m unable to let them go. Firstly, I hope to give talks and walking tours of the area to bring their stories back to life. In time I hope to take lessons into schools, make a documentary and write a novel based on their experiences.

Ordinary people in history, to me, are far more fascinating than kings and queens. It may be harder to piece together their lives from the fragments of information that have survived, but we are all the richer for it when we do.

My dissertation, listing all the resources from LMA that I used, was published by the Open University.

Further reading

- Chance, William, Children under the Poor Law: Their Education, Training and After-Care; Together with a Criticism of the Report of the Departmental Committee on Metropolitan Poor Law Schools (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co, 1897)

- Mornington, Walter and Frederick J Lampard, Our London Poor Schools: Comprising descriptive sketches of the schools with a map (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1898) with map insert of the London poor law school board districts

- Macnamara, T.J., Children under the Poor Law: A Report to the President of the Local Government Board (London: Darling & Son, 1908)

- Dyos, H. J., Victorian Suburb: A study of the growth of Camberwell (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1961, fifth impr. 1986)

- Hendrick, Harry, Children, childhood and English society 1880-1990 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- Murdoch, Lydia, Imagined Orphans: Poor Families, Child Welfare, and Contested Citizenship in London (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006)

- Ordnance Survey Map [1:25] London 102:3 Camberwell & Stockwell 1913 (Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps, 1990)

- Ordnance Survey Maps [1:25] London 103.3 Peckham 1914 (Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps, 1990)

- Ordnance Survey Maps [1:25] London 117.3 East Dulwich & Peckham Rye 1914 (Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps, 2nd edn 2015)

- Ordnance Survey Maps [1:25] London Sheet 127.3 Dulwich Village 1913 (Consett: Alan Godfrey Maps, 3rd edn 2006)

- Peter Higginbotham’s Workhouses website