Wren's masons

The Strongs and the Rebuilding of London after the Great Fire

The Strong family were a successful dynasty of masons who made the most of the opportunities available in London after the Great Fire. They were talented and reliable craftsmen who were trusted by some of the most famous architects and designers of their age. They carved a place for themselves in the world through their skill and enterprise and the buildings which they raised – including St Paul’s Cathedral, some two dozen parish churches in London and the suburbs of the City, and the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich - stand today as testaments to their expertise. Dr Ian Stone, looking to learn more about their lives and careers, found one of the richest seams of material in the records of the Masons’ Company. In this article he writes about the history of the family and the buildings they worked on, as well as what their careers can tell us about the history of the construction industry in seventeenth and early eighteenth century London.

Thomas (c. 1632-81) and Edward Strong senior (1652-1724) were brothers who were born into an established family of stonemasons and quarry owners in Oxfordshire. With Edward senior’s son, Edward junior (1675/6-1741), they were three of the most famous stonemasons and contractors ever to have worked in London. Between them they worked on St Paul’s Cathedral, some two dozen parish churches in London and the suburbs of the City, the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and many other fine buildings which were raised in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London. They were also three of the most important members of the Worshipful Company of Masons at a time when the Company was carving out a new role for itself in the City of London. All three men became wealthy through their labours, and all three rubbed shoulders with some of the most eminent architects, artists and commissioners of their age. They are well known to architectural historians, but little known to a more general audience. The historian looking to learn more about their lives and careers will find one of the richest seams of material in the records of the Masons’ Company, managed by London Metropolitan Archives, and available for access at Guildhall Library.

Thomas had taken over the family business in 1662 when his father died and, three years later, he began work at Trinity College Oxford, building lodgings for students to the designs of a promising young astronomer called Dr Christopher Wren. Thomas would probably have continued in a successful career as a mason and quarry owner in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire were it not for the Great Fire of London in 1666. By the time that the Fire had burned out, it had destroyed 13,000 houses, 44 company halls (including the recently and expensively rebuilt Masons’ Hall), St Paul’s Cathedral and 87 parish churches. About eighty per cent of the built-up area within the city walls was incinerated and the cost of the damage was estimated at somewhere between eight and ten million pounds. For someone as enterprising as Thomas Strong, however, this was an opportunity too good to miss, and in 1667, at the age of thirty-five, Thomas moved to London taking several masons with him. Other masons from Oxfordshire, for example Christopher Kempster and Ephraim Beauchamp, also did the same. In his first few years in London, according to a later memorandum drawn up by his brother Edward, Thomas worked hard on the rebuilding of houses and livery company halls, and he supplied ‘great quantities’ of stone from his own quarries to other masons.

Hitherto, the Masons’ Company, theoretically at least, had decided who had the right to practice the craft of masonry within London, and the terms on which they were to work. But the Company’s authority was waning as the city’s population grew and the traditional economic model of the medieval town, that of the independent artisan as master of his own workshop, was replaced by the emergence of a new economic archetype, one in which larger manufacturers subcontracted their labour. The financial demands of the Stuart kings, whether for the Ulster plantation, civic charters or ship money, and the subsequent civil wars, had driven many companies close to ruin. Between 1639 and 1646 the Masons’ Company posted a financial loss in every year apart from one, when, in 1644-45, it recorded a surplus of just 27 shillings.

In some ways, the provisions made for rebuilding London after the Fire boded well for the Masons’ Company. The two Rebuilding Acts of 1667 and 1670 provided for the reconstruction of St Paul’s Cathedral and fifty-one parish churches. The Acts also insisted on the use of brick and stone for the exteriors of buildings. With such demand for stone construction, surely now the role of the Company as the regulator and quality-controller of masonry would be enhanced? At the same time, however, there was an equally great demand for labour. To meet this demand the First Act relaxed the restrictions on who might work in London. Now anyone, whether free of the Masons’ Company and the City of London or not, could work in the city for a period of seven years, at the end of which time they would acquire the freedom of the city and have the same rights as other citizens. This was a provision that weakened the Company’s authority a great deal. What now was the point of joining the Company with all the costs and responsibilities that membership entailed?

As far as Thomas Strong was concerned, however, membership must have offered him something, for on 8 September 1670 Thomas became free of the Masons’ Company and the City of London by redemption (payment). Just over one year later, he was clothed in the company’s livery. There were perhaps two advantages of membership obvious to Thomas. First, by joining the Masons’ Company, Thomas could bind apprentices. Indeed, the records of the Company show that he quickly bound two, so he must have had plenty of work in these years. It is also, perhaps, significant that Thomas became a freeman of the Masons’ Company just months after the passing of the Second Rebuilding Act. Perhaps Thomas believed that he would be better placed to win some of the many building contracts which would follow this Act were he a member of the Company?

Whether that was the case or not, in 1672 Thomas was awarded his first major contract in London when, with his fellow mason Christopher Kempster, he was given charge of the masonry work in the rebuilding of St Stephen Walbrook, London ‘by the direction of Sir Christopher Wren’. St Stephen’s, one of the most beautiful of Wren’s parish churches, took eight years to complete, without its spire, at a cost of £7,652; perhaps as much as £1,600 of which was paid to Thomas. Thereafter, other contracts followed. Thomas was the lead contractor for two other Wren churches: St Benet Paul’s Wharf, which he began in 1677, and St Augustine Watling Street, which he began in 1680. Thomas’s biggest contract, however, was awarded in 1675 when, along with Joshua Marshall, the king’s master mason and the builder responsible for the Monument and Temple Bar, Thomas was appointed as one of the two mason-contractors to rebuild St Paul’s Cathedral. On 21 June 1675, Thomas laid the Cathedral’s foundation stone with his own hands, and three years later, he had a team of at least thirty-five men employed at the site.

Thomas died wealthy, but unmarried and suddenly, ‘about Midsumer’ [24 June] 1681, and his brother, Edward, took over Thomas’s business. At Masons’ Hall, in October 1681 and May 1682, Thomas’s two apprentices, Richard Cowdrey and John Miller, were turned over to Edward. Edward also completed his brothers’ contracts at St Benet and St Augustine (1684), and he continued to work at St Stephen Walbrook. Over the next two decades, Edward also won the contracts to rebuild six more parish churches in London: St Mildred Bread Street (1681–7), St Clement Eastcheap (1683–7), St Michael Paternoster Royal (1685–94), St Mary Magdalen Old Fish Street (1683/4–7), St Mary Aldermary (1681–2), and St Vedast-alias-Foster (1695-1701). These projects, however, were dwarfed by Edward’s commitments at St Paul’s Cathedral where, again, Edward had taken on Thomas’s responsibilities. Over the course of the next twenty seven years, Edward completed the work on the east end and the north portico which his brother had started. He also built the north side of the nave and the north-west quarter of the dome. On 26 October 1708 (three years before the work at St Paul’s would officially be declared complete), Edward laid the last stone on the lantern on the Cathedral’s dome, meaning that he was one of very few men who were engaged from beginning to end in the Cathedral’s reconstruction.

Edward had, like Thomas, taken contracts outside London. In 1683, for example, he had begun work at Winchester Palace. In the 1690s he took on two large-scale projects immediately to the south-east of London. The first was the construction of Morden College on Blackheath, founded by Sir John Morden, a merchant, at a cost of £10,000 (1694/5). The second was the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich where Edward began work in 1696. Wren, Nicholas Hawksmoor, and Sir John Vanbrugh were all involved in the designs for this enormous project which, in the end, took over fifty years to complete. Here, Edward went first into partnership with Thomas Hill, then with his brother-in-law Ephraim Beauchamp, before finally working with his son, Edward junior (d. 1741), on the site.

Father and son also worked together at St Paul’s. Edward junior begun work on the lantern in 1706, he also laid the marble floor beneath the dome and transepts and carried out remedial work under the dome caused by differential settlement. It was, too, in partnership that Edward senior and Edward junior took on the contract to build Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. For seven years from 1705, Edward senior and his son were responsible for building the main pile at Blenheim to Vanbrugh’s designs. In 1712, however, the money for the project ran out and father and son became embroiled in a ten year legal dispute to recover money that they were owed by Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough.

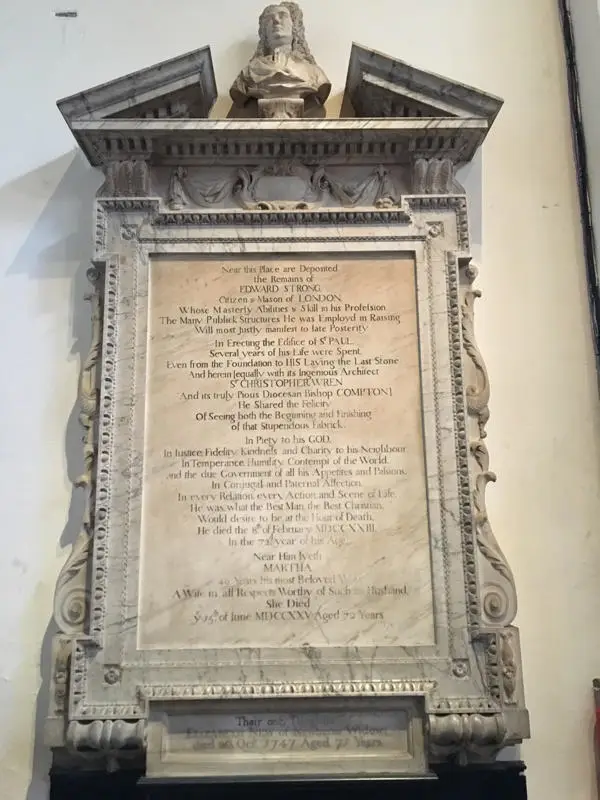

Shortly after work came to a halt at Blenheim, Edward senior settled in St Albans, Hertfordshire. He died on 8 February 1724, at the age of seventy-one, and was buried in the parish church of St Peter in St Albans where a very impressive memorial to his memory was raised. Edward had prospered. At the time of his death he owned at least eighteen properties in London and Hertfordshire, in addition to the family property he had inherited in Oxfordshire. Edward junior took over the family business. He took contracts at a dozen or so London churches – including at least six of the new Commissioners’ churches – in addition to the work he continued at St Paul’s Cathedral and Greenwich Hospital. He, too, was a successful businessman who accrued great wealth. With their wealth and land both father and son acquired status, too, styling themselves as ‘gentleman’ and ‘esquire’. Indeed, Edward junior’s daughters married into the gentry, two acquiring titles, and his great grandson married the daughter of the fourth duke of Marlborough.

In their wills, however, both Edward senior and Edward junior defined themselves as a ‘citizen and mason’ of London, and Edward senior was described in this way on his memorial. The Masons’ Company was clearly important to father and son. In 1694, Edward senior became warden, and in 1696 master of the company. That is to say, he served as warden and master while managing work St Paul’s Cathedral, St Vedast-alias-Foster, Morden College and Greenwich Hospital. He was, too, the Company’s treasurer between 1693 and 1716. Edward junior was warden in 1712 and 1715, and master in 1718, during which years, work had begun at the Queen Anne churches. Edward senior and junior both held office in the Company when they were evidently busy men. Being members and officers of the Company must, then, have meant something to them. They would not have taken the trouble otherwise. The records of the Company bear witness to the central role they played in corporate life over a period of some fifty years, and they enable us to reconstruct a detailed picture of their lives and careers.

The Strong family were a successful dynasty of masons who made the most of the opportunities available in London after the Great Fire. They were talented and reliable craftsmen who were trusted by some of the most famous architects and designers of their age. They carved a place for themselves in the world through their skill and enterprise and the buildings which they raised stand today as testaments to their expertise.

I have recently written biographies of Thomas and Edward Strong senior for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. This article is based on a lecture which I gave to the Worshipful Company of Masons in October 2019. The lecture, with much more detail about the Strongs and images of the work they completed, is now available on YouTube.