The Enchanted Interior Exhibition Catalogue - An Extract

In the extract below, adapted from her essay in the exhibition catalogue, The Enchanted Interior’s curator Madeleine Kennedy reveals the ideas and convictions that shaped the project, touching on the sinister dimension of enchantment and the motif of the ‘gilded cage’. She goes on to consider the power of confronting historic idealisations of this theme with works by female artists which resist its intoxicating effects, destabilising the allure of women typecast as victims, captives, and objects, and offering an alternative vision of enchantment.

In Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, we encounter the disturbing idea that the extent of something’s superficial or material beauty can entirely conceal the extent of its evil.[1] The protagonist of the story, Dorian Gray, is granted eternal youth in exchange for his soul, so that his physical beauty remains untainted by his wrong-doing, whilst a portrait of him hidden in the attic becomes more grotesque with each immoral act. As readers, we are exposed to the possibility that the beautiful and the sinister are symbiotic; that moral corruption can wear a beguiling face whilst seducing us into its control.

This is not unlike the story behind The Enchanted Interior.

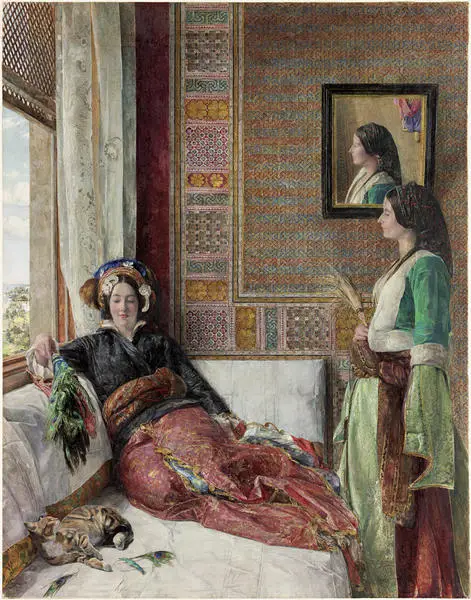

The project began as a way to showcase two stunning works in the Laing Art Gallery collection: Laus Veneris (1873-5) by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, and Hhareem Life, Constantinople (1857) by the British Orientalist John Frederick Lewis. Both paintings are of national significance: the first as one of Burne-Jones’ greatest masterpieces, and the second as one of the best-preserved examples of Lewis’ harem scenes, many of which have faded considerably over time. Each painting – the first in oil and the other in watercolour – shows a richly decorated interior, occupied by a central female figure and one or more attendants. The material luxury is striking, the setting palatial, the women adorned in glorious silks and ornate patterns.

But as in the story of Dorian Gray, there is a sinister reality hidden just below the surface of these scenes. In the case of Laus Veneris, the main figure is the goddess Venus, heartbroken and condemned to remain in her shrouded lair as her lover Tannhäuser abandons her. In the case of Hhareem Life, Constantinople Lewis plays into Victorian prejudices about the Middle East as a place where one man may ‘own’ multiple women, often assumed to have entered the harem as slaves. In short, both paintings show women who are in some sense trapped in their luxurious surroundings. As captured in the lyrics of a popular ballad from 1900:

She's only a bird in a gilded cage,

A beautiful sight to see.

You might think she's happy and free from care,

She's not, though she seems to be [2]

This exhibition traces the motif of the ‘gilded cage’ as it was crystallised in the work of nineteenth-century artists such as Burne-Jones, Lewis and their peers; as it haunts the work of twentieth-century artists; and as it is itself captured and rethought by contemporary artists who seek to expose and escape its sinister implications.

***

One remarkable quality shared by many of the nineteenth-century paintings at the heart of this exhibition is their ability to blind us to their veiled menace. So many works by the Pre-Raphaelites and their peers take inspiration from stories of women imprisoned in towers, tormented by suitors, abducted, or forced into marriage,[3] yet they remain among the most popular and beloved paintings in the country. Their masterful rendering of paint still seems to radiate light now, their rich symbolism rewards close-looking, and their dreamlike scenes of romance and melancholy catch our imagination. They are, without doubt, enchanting objects.

Indeed, as this project evolved, it became clear that the unnerving confluence of the sinister and the beautiful are inherently intertwined in the very idea of enchantment. Although we generally understand enchantment as something positive, its definition spans a spectrum of meanings from the innocuous to the occult. Among the synonyms of ‘enchanting’ are captivating, hypnotising, bewitching, and entrancing. To enchant is not just to charm, but to intoxicate, entrap or coerce. As such, enchantment is tied up with ideas of agency, power and control. Not the overt control of authority or force, but an insidious, invisible, seductive control that acts upon its victim without their knowledge: poisons the blood stream, controls the mind, or pollutes the atmosphere.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the idea of enchantment has long been associated with women, traditionally stereotyped as skilled in the art of persuasion over brute strength or political strategy. In our fairy tales, myths and stories, it is often women who enchant: who use their charms to exert control over the innocents that get tangled in their web. This is the trope of the femme fatale (deadly woman); the ‘enchantress’ with unnatural, prophetic, or witch-like power. The sirens’ song that induces shipwrecks is a form of enchantment, as is the century-long slumber inflicted upon Sleeping Beauty by the evil queen.

Laus Veneris is also the story of a captivating femme fatale. In the poem of the same name by Algernon Charles Swinburne, which influenced Burne-Jones, Venus is portrayed as ensnaring men and leading them to their death:

Their blood runs round the roots of time like rain:

She casts them forth and gathers them again;

With nerve and bone she weaves and multiplies

Exceeding pleasure out of extreme pain [4]

If you enjoyed this extract adapted from the exhibition catalogue, you can now order your limited edition on our online shop. Orders will be shipped soon. Ordering your copy now will support Guildhall Art Gallery and ensure that you receive it as soon as possible.

Madeleine Kennedy is the curator of The Enchanted Interior exhibition and editor of the accompanying publication. Now working as a freelance curator, she began developing The Enchanted Interior whilst working at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, where the exhibition was first shown from October 2019 to February 2020. She has previous experience in curatorial teams at Tate Britain, Hatton Gallery and Firstsite Gallery, and has a masters degree in curating from the Courtauld Institute of Art. Notable recent exhibitions include Modern Visionaries: Van Dyck and the Artist’s Eye (curated in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery) and Exploding Collage. She has also written widely for art journals and artist monographs, and is currently undertaking doctoral research at the University of Oxford, specialising in the philosophy, history and theory of exhibition-making.

[1] Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890.

[2] Arthur J. Lamb and Harry Von Tilzer, A Bird in a Gilded Cage, 1900.

[3] This refers to, for example, The Lady of Shallot, depicted by Waterhouse and Holman Hunt among others; Penelope and the Suitors by Waterhouse; Proserpine by Rossetti and Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Holman Hunt.

[4] Algernon Charles Swinburne, Laus Veneris, 1866.

[5] Swinburne, Laus Veneris, 1866.