The journey of the letters

Unwrapping the journey of these letters is a strange story, from when the ink first touched paper at Wentworth Place in Hampstead, to their travels across continents and eventual return to Wentworth Place, now Keats House. They passed through the hands of some unusual characters but thankfully survived, providing a window into the lives and feelings of two women whose voices would otherwise have been lost to us. These letters are now being published online here.

The letters

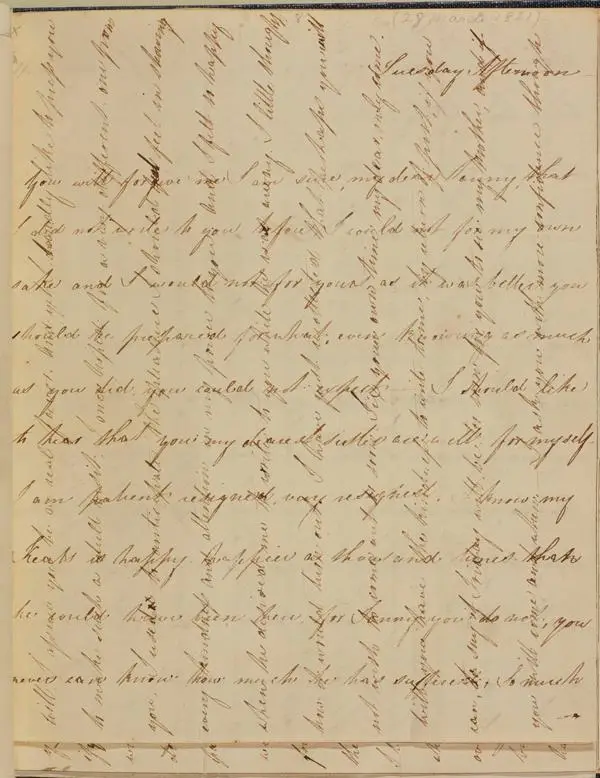

The letters from Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats were written over four years, starting the day after Keats left London for Rome where they hoped he would recover from consumption. There are 31 letters, now held together in one volume. The letters are neatly written and very readable even where she has used cross-hatching, a common way to save paper.

She writes on woven paper, expensive at the time, which was likely brought from a stationers as the paper size differs between letters. The ink is Iron Gall, a purple-black or brown-black ink, which was in standard use across Europe for hundreds of years. Where it still exists, Fanny Brawne used a black wax for her seal. She makes some references to her writing in a few of the letters.

"‘ – It will ever remain a mystery to me whether it is possible to read a letter written in this greasy ink, I have all but sworn at it –’"

Fanny Brawne, February 1824

Fanny Brawne was Keats’s fiancée. While she nursed him at Wentworth Place, just before he left for Rome where they hoped he would recover from Consumption, he asked her to write to his little sister. Fanny Keats was seven years younger than Keats and after they were orphaned she came under the control of her domineering guardians Mr and Mrs Abbey.

By June 1824 Fanny Keats had come of age and this is where the correspondence ends. She could now choose freely to spend time with her friends. In 1826 she married Valentine Llanos (himself the subject in several letters as Fanny Brawne was instrumental in bringing them together) and a few years later the couple move into Wentworth Place. They lived on the side of the building Keats and Brown originally shared and, as Fanny Brawne was still living on the other side, the two friends became neighbours. But, with their family growing, Fanny and her husband eventually left Hampstead and moved to Spain. As an indication of how precious these letters were to her, when their luggage was confiscated at customs and never returned, it is only because she had kept them and other family manuscripts with her that they survive today.

The letters remained with her in Madrid, until December 1890.

Boston, America

During the years the letters were safely stored in Madrid, Keats’s poetry had become increasingly popular and he was well on his way to becoming a famous poet. One biography had been written and artefacts related to his life started to be of great interest to his fans.

One of these fans was Fred Holland Day, an eccentric publisher and photographer with independent wealth. He dedicated himself to gathering a unique collection of Keatsiania. With the help of fellow Keats enthusiast Louise Guiney, he tracked down Keats’s sister and wrote to her. They exchanged a few letters which Fanny, by then 86 years old, dictated to daughter Rosa. A month after this contact she died. Fred Holland Day continued to write to Rosa and visited the family. When he left, he took the 31 letters with him, with the understanding he would publish them immediately.

However, they were not published for another 43 years, and the attempts of three separate women researchers failed to persuade him to make them public. These researchers were interested in Fanny Brawne’s perspective and hoped to negate the criticism following her death and the publication of the love letters she received from Keats. Keats’s passionate jealousy had been interpreted as Fanny Brawne’s fault, with her being ‘shallow hearted’ and having caused Keats great unhappiness before he died.

The letters do give a much richer account of Fanny Brawne’s and Keats’s deep and mutual affection. The first attempt to discover this was made by Louise Guiney. She had been instrumental in helping Day acquire the letters, but he would not let her read them at first, and later wouldn’t let her include their content in her academic talks about Fanny Brawne.

The second attempt to access them was by a fellow Keats collector, Amy Lowell. Lowell was a wealthy and popular American poet from Massachusetts. She was an avid collector of Keatsiania and contributed a great deal of material to public collections. She was also instrumental in raising funds to save Keats House and open it as a museum.

In 1925 she published a book on Keats, in which she wanted to vindicate Fanny Brawne, and she included some extracts from these letters. But she was not allowed to reveal her source and many critics did not believe they were genuine quotes. That she even had some extracts to include was amazing, as she had spent four years trying to persuade Day to show her the letters and, while never outright denying her access, he never properly allowed her to see them.

As one example, in March 1922 she managed to arrange a visit with him, which he insisted be at his bedside as he was by then living as a reclusive hypochondriac. He heard she had a physically large build and had all the furniture removed from his room other than his bed and a small wooden chair. She stood for 3 hours. On another visit he let her see some of the letters, but taped them between sheets of glass so she couldn’t read them fully or even see to whom they had been written.

Day was a procrastinator, moving between projects without finishing them. He often gave the reason that he had not been given permission by Fanny Brawne’s children to publish the letters, though this was forthcoming years later when her family were told of their content. He also disliked the idea of generating gossip which would detract from Keats’s poetry. Unfortunately he didn’t seem motivated by helping readers better understand the lives of Fanny Brawne or Fanny Keats.

There was a final failed attempt to access these letters by Dorothy Hyde, a graduate researcher interested in Charles Brown and Fanny Brawne. She realised after one visit with Day that it was hopeless. For a time it was even thought he may have sold the letters, but in 1928 he anonymously sent his first enquiry to the curators at the newly opened Keats House.

Returning to Wentworth Place, now Keats House

After an initial correspondence between Day and the curators at Keats House it was unclear if he would commit to donating any of his collection. Louise Guiney recommended Keats House as the right place to hold them and a few months before her death had written to Day:

"‘I should like a Fanny Brawne letter or two to be kept for-ever in the house where they were written.’"

Louise Guiney

Over five years, manuscripts were promised to Keats House but never sent. Eventually in 1933 Fred Holland Day died and left a typically vague and confusing will. Fortunately, those at Keats House were able to persuade his executors that his intention had been to donate Fanny Brawne’s letters. Among some other items, they finally arrived at Keats House on 28 August 1934. After 110 years, the letters were back in Hampstead in the house where many had been written.

Fanny Brawne’s letters at Keats House

As part of the gift, Fred Holland Day asked for the letters to remain sealed until 1961. However, under British law the copyright of unpublished manuscripts belonged to the writer’s heir. Fanny Brawne’s granddaughter was shown the letters, and very much wanted them published. They were reproduced in their entirety in 1936, in a book by Fred Edgcumbe, the curator at Keats House.

This transformed Fanny Brawne’s reputation from being cold hearted, into what Edgcumbe described as ‘a young woman of remarkable perception and imagination’. However, this was the 1930s and Fanny Brawne was still judged by her relationship with Keats. Edgcumbe’s full quote is:

‘These letters show Fanny Brawne, who was but twenty years of age, as a young woman of remarkable perception and imagination, keen in the observance of character and events, possessing an unusual critical faculty, and intellectually fitted to become the wife of Keats.’ [Quote]

The Keats House project to digitise these letters and publish them online is a way to open conversations about the lives of the women who lived at Wentworth Place, and update the way we talk about the lives and motivations of women.