West Wickham Common heritage

On arrival, West Wickham Common looks similar to other urban woodlands; but as visitors delve a little deeper they discover layers of history and heritage unfolding in front of them.

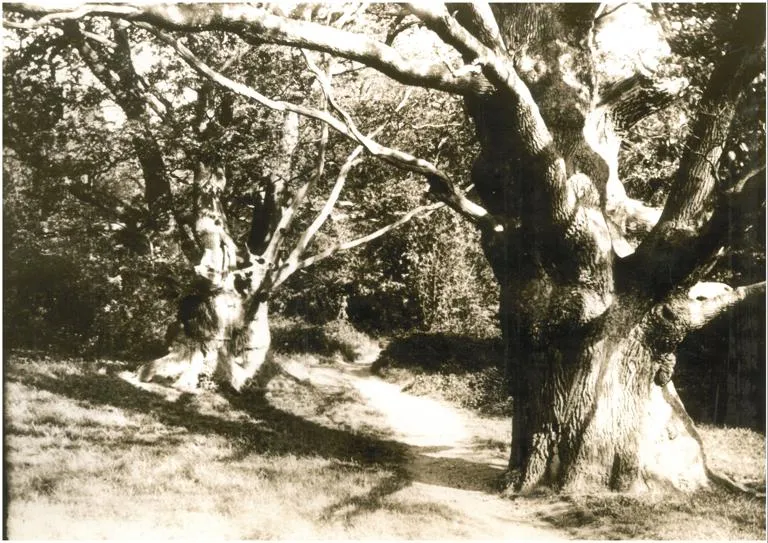

Enormous veteran oak pollards are scattered across the side of a hill, which entices you up to an open heathland. Carefully managed over several generations, these magnificent trees are now the ancients of the forest. There are also many undulations, ditches and banks visible throughout the heath today but when were they dug and why are they here?

Heritage features

The origin of the assemblage of banks and ditches on the heathland have fascinated archaeologists and historians for nearly a century. Experts have used their knowledge of other similar looking sites to make suggestions about the age and purpose of some of these features. A deep defensive ditch to either side of an entrance causeway forms an incomplete ring which may have been further fortified by a row of upright spiked logs, called a palisade. This could be an incomplete Iron Age hill fort (800BC – AD43) but no one knows why it was never finished. Long straight banks continue on to Hayes Common and are probably part of a Medieval field system (1066 – 1540).

Some earth mounds may be the remains of artificial rabbit warrens. A map of 1772 shows warrens in this area and local place names such as “Coney” (meaning rabbit) or “The Warren” strongly suggest a link.

Scattered across the western slopes are the remains of a population of pollarded oak trees. Branches have been harvested from the trees for centuries to provide firewood and leafy forage for cows and sheep. By cutting the branches beyond the reach of grazing animals (pollarding) new growth was guaranteed and the resulting rejuvenation of the trees prolonged their lives. Several of these ancient oaks are still thriving and are thought to be more than 600 years old. One was made famous by the Victorian artist J.E. Millias in his painting The Proscribed Royalist 1651.