Homesteading

GLC housing scheme 1977-81

The Greater London Council Homesteading scheme was introduced by the Conservative administration of 1977-81 as a solution to the problem of what to do with the poor quality housing for which the GLC was responsible while at the same time promoting home ownership. It is vividly brought to life by Tess Pinto a post graduate research student from Royal Holloway, University of London who draws on a diverse range of material relating to the scheme held at LMA to paint a picture of an important period in the GLC’s history which is not widely discussed or understood.

Politics and policy

The Greater London Council (GLC) was London’s city government, responsible for providing services, housing and planning across the city from 1965 to 1986. Due to Ken Livingstone’s administration of 1981-6, the GLC has a reputation as a hotbed of radical left-wing politics. Under Livingstone’s leadership, the GLC sought to empower minority groups, and clashed publicly with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government over fares, unemployment, rate-capping and the role of local government itself. But accounts which focus solely on the final administration of the Council before its abolition by Thatcher in 1986 tend to obscure the fact that the GLC was politically contested - controlled alternately by the left and right throughout its existence - and responsible for administering a city which was similarly divided between its left-leaning centre and Conservative peripheries.

Like Livingstone’s ‘new urban left’, the GLC administration of 1977-1981 also rejected the statism and consensus politics that had characterised the post-war era, but this rejection was part of a very different kind of political project. In 1977, the Conservative’s won control of County Hall by a huge margin, and over the next four years the council leader Horace Cutler – property developer, personal friend of Thatcher, and member of the right wing pressure group the Monday Club – oversaw the emergence of the New Right in London’s government.

In the months running up to the 1977 election, the Labour-led GLC had been embroiled in a huge housing scandal after the documentary Goodbye Longfellow Road exposed corruption at the heart of the housing department, and dire council housing conditions in older council housing stock. Despite large-scale house building and ‘slum’ clearance programmes in London since the Second World War, huge areas of housing were empty, dilapidated and blighted, and the long lapse between inception and completion meant housing schemes designed years earlier were only just being built in the 1970s. The scandal was a timely boon for the Conservatives, who used the opportunity to make a strong pitch for housing and local government reform. Once in power, Cutler began the process of transferring GLC owned estates to the local boroughs, axed the housing branch of the architect’s department, and reintroduced council house sales and home loans.

Homesteading

Amongst this raft of transformative measures was the introduction of a new Homesteading policy. Unlike sales and loans, Homesteading aimed to directly address abandonment and physical decay in the city. The scheme sold dilapidated council-owned houses on a 100% deferred mortgage to first time buyers who were already living in London, and ‘who were without the resources to buy an already improved property, but were enthusiastic about restoring a run-down house and were willing to do much of the necessary work themselves’. It gave Homesteaders three years to renovate and modernise their own homes without repaying their mortgage.

Homesteading was a shrewd solution to the problem of what to do with the poor quality housing for which the GLC was responsible. Cutler’s GLC was ideologically committed to dismantling council housing and rolling back the state, so renovating the properties for council tenancies was not an option. Neither was redevelopment: both Cutler and the Chair of the Housing Committee George Tremlett were aesthetically and politically opposed to mass housing schemes and the demolition of older buildings – a sentiment which reflected a public shift in values during the previous decade. There was now a broad public consensus that Victorian terraced housing (which comprised much of the housing stock in question) was desirable, fit for purpose and part of a national heritage. Homesteading therefore presented a way to deal with council-owned housing that could not easily be sold on the market, but which the GLC no longer had any inclination to develop. The popularity of the scheme was a clear demonstration of the demand for both home ownership and traditional types of housing.

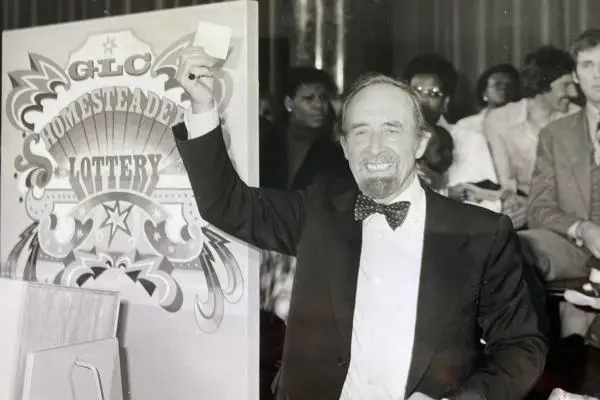

On 26 September 1977 a Homesteading Lottery was held at County Hall, which drew big crowds. Horace Cutler, who manned the tombola and personally congratulated the winners, described the response as ‘staggering’ and claimed the scheme was providing a ‘great new opportunity to many London couples struggling to buy a home of their own at a price they can afford.’ 11,000 applicants entered the draw, and on the night there were 300 winners. To meet the massive demand, a second lottery was held on the 7 December, and a further 200 winners were drawn from over 15,000 applicants. Winners were then matched with properties – the majority of which were in East and South East London. This was a tricky process, as houses of the right level of dilapidation needed to be found, and many winners wanted to live in more desirable areas of West and South West London.

Second phase

In response to the shortcomings of the initial scheme, the Housing Committee developed a second phase of Homesteading in early 1978. The committee allocated a further £3 million to spend on buying up suitable houses from the market for re-sale to applicants. The new phase was advertised under the slogan Find Yourself a Homestead – ‘If you find a dilapidated vacant house in London which is being sold and which you would like to buy - tell us about it.’ Properties needed to be valued at less than £19,000 and require at least £2,000 worth of work at contractor’s price. The scheme was also extended to include applicants who had previously moved away from London on a GLC Home Loan to a New or Expanding Town, and who now wanted to return. This was a direct reversal of a long-term strategy going back to the strategy of the planner Patrick Abercrombie, which had been to move people out of the city from the early 1940s onwards.

In 1979 a Directorate of Homeownership was created, which brought all of the GLC’s homeownership policies under one roof. Council house sales, home loans and Homesteading were all overseen by the same department which was based on the Albert Embankment, about half a mile along the Thames from County Hall. The Directorate opened a permanent Homesteading exhibition space, with a ribbon cutting ceremony by the Minister of Housing John Stanley in 1980, and a dedicated home sales shop. The Directorate also managed a Homesteading themed stall at the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition in Earls Court in the same year, and held a competition to win a Homestead, gas cooker, fridge and £500 of decorating materials and tools. The 2,700 entrants had to select from a list of manual jobs which were the most urgent to be undertaken in a homesteading property, and then finish the following sentence in 15 words – ‘Homesteading is good for London because…’

There were further plans to extend the Homesteading scheme thanks to capital raised from GLC council house sales, and 1981 began with a ‘Homesteaders Hoe-Down’ at County Hall – a big barn dance to celebrate those who had taken part. Identity cards for Homesteaders were also in the process of being issued when the scheme was brought to an abrupt halt, as the GLC elections of May 1981 saw Ken Livingstone’s Labour administration installed in County Hall by a slim margin, and Homesteading and all other council house sales were brought to an immediate halt.

USA origins

Like much of the urbanism in vogue during the period, the idea for Homesteading was taken from the United States, where municipal governments and non-profit organisations had overseen urban Homesteading projects in North American cities since the early 1970s. Homesteading itself was inspired by earlier self-help housing schemes and took its name from the Homesteading Act of 1862, which had encouraged settlers to the western frontier. Whilst other schemes were run by and for the working-class, the white middle-classes were explicitly targeted by government schemes. Senator for Delaware Joe Biden, which had been the first state to introduce Homesteading legislation in 1973, celebrated the return of these people to the inner city from which they had fled in the inter-war period.

Who were the Homesteaders?

In London, the Homesteaders were a less explicitly white, middle class group. GLC Homesteaders were generally people already living in inner London, who could not afford to move to the suburbs and were at the end of the municipal housing queue. Whilst there is no data available on ethnicity, 515 households took part in a survey which shows that the majority were young couples who had mostly lived in privately rented flats or bedsits. Around 30% were, or had previously been, local authority tenants. 70% had a gross annual income of less than £7,000 a year, when average gross earnings were around £7,500. While the very poorest would have been excluded from taking part, Homesteading was certainly not aimed exclusively, or even predominantly at wealthy suburbanites as it had been in the States. Photographs also indicate that Homesteaders may have been a more ethnically diverse group than their North American counterparts, and it is possible that the scheme would have appealed to ethnic minorities who struggled to access council housing, feared racial violence on large estates, and faced discrimination in the rental sector or from private mortgage lenders.

The archives

Homesteading is vividly brought to life in London Metropolitan Archives, which holds a diverse amount of material relating to the scheme. Identity cards, adverts, posters, photographs, leaflets and council minutes all help to paint a picture of an important period in the GLC’s history which is not widely discussed or understood. Both the Homesteading scheme and Cutler’s GLC have also been overlooked in urban histories of the period. Whilst Homesteading responded to its local context in London, it also indicates a deep ‘unsettling’ of the post-war settlement, and its emphasis on individual enterprise, home ownership, and celebration of heritage embodies the kinds of cultural attitudes that would come to characterise urbanism in the 1980s.

Final word

Homesteading as a concept has not been widely practiced elsewhere in the UK. Newcastle, Bristol and Liverpool have all experimented with their own versions of the idea since the late 1970s, though none have been come close to the scale of the scheme in London, which facilitated the conversion of around 1,500 properties over four years, and would undoubtedly have been expanded had the Tories won the 1981 GLC election. As a concept, it would not work in London in the same way today: the dilapidated terraced housing that the original scheme required in quantity simply no longer exists. Homesteading in London is therefore set to remain an unusual and unique part of post-war history.

Sources

- Homesteading: An Introduction to the Greater London Council Homesteading Scheme, 1979 - GLC/DG/PUB/01/121

- Homesteading Scheme to Renovate Derelict Housing: Guide and Entry Form, 1980 - GLC/DG/PRB/08/0513

- Rescuing Old Homes - GLC/DG/PUB/01/140/1284