London’s Literary Merchants

LMA’s collections are full of intriguing records of seventeenth-century merchant life. We might think, for example, of the sixteen books (CLC/509/MSS05100–05110) of Sir William Turner (1615–93), a London textiles merchant, and a leading figure in the Merchant Taylors’ Company. This collection of handwritten volumes, many still in their original bindings or wrappers, includes expenses books, cash books, sales books, letter books, purchase books, stock books, and journals. Together, these sixteen books constitute one of the most extensive surviving business archives from the early modern world.

We might also think of the ‘Italian’ account-book (CLC/B/227/MS35025) of Daniel Harvey (1587–1647), younger brother of the physician William Harvey. This beautifully bound volume, made up of nearly 600 leaves, contains accounts scrupulously kept in the double-entry, or ‘Italian’, fashion. We might think, too, of the three account-books (CLC/B/013/MS23953, CLC/B/013/MS23954, CLC/B/013/MS23955) of Richard Archedale (c. 1574–1638), a draper and provisions merchant, with premises on Elbow Lane. These books provide revealing insights into the seventeenth-century wine and sugar trades in particular.

These are exactly the kinds of commercial records that we would expect to find. There are, however, also more unusual items amongst the LMA collections: documents that provide insights into not only seventeenth-century merchants’ commercial lives, but also their literary and cultural lives. I’ve spent the past eighteen months searching for such records as part of a larger research project on early modern merchants and their books.

That has meant trawling through inventories, account-books, letters and wills (and also increasingly regular visits to Northampton Road). In this essay, I present some of the findings of that research. What emerges is a very different picture of London’s seventeenth-century merchants to the one normally presented. Many of the city’s merchants seem to have collected books on a significant scale and to have been much more closely involved in the literary world than historians have previously thought.

This essay introduces three seventeenth-century merchant libraries and their collectors. We will meet Robert Stanier, a half-German merchant and book collector from Bethnal Green. We will also meet the Clitherows of Boston Manor. Across successive generations, this family amassed an enormous collection of books, including a pair of unique seventeenth-century literary manuscripts—both of which still survive at LMA. We begin, though, with a collection of mostly Italian books from Lime Street, which belonged to Anthony Abdy.

Anthony Abdy’s Italian Books

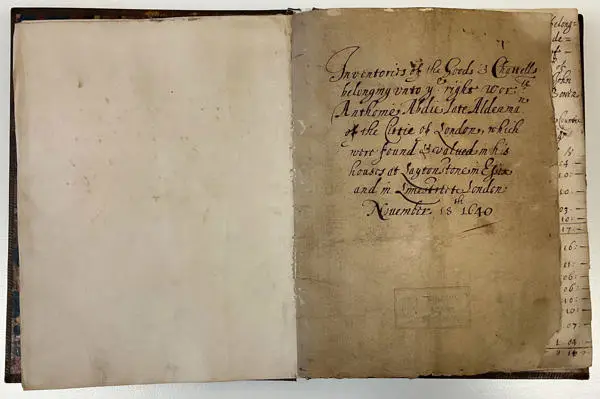

Anthony Abdy (d. 1640) was an alderman, a sheriff of London (from 1630 to 1631), and a leading member of the Levant and East India Companies. We know about his library thanks to an inventory (CLC/521/MS03760) of his goods and possessions prepared on 18 November 1640 just a few days after his death.

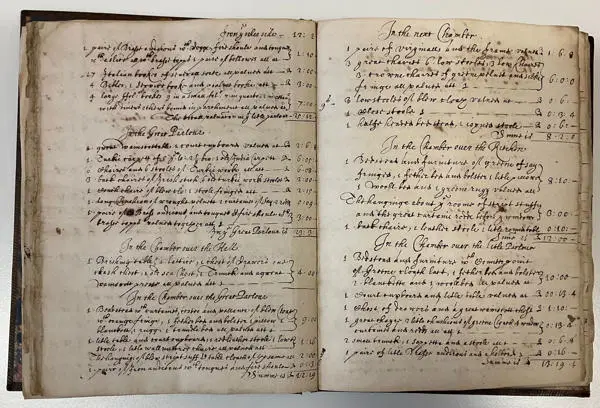

The inventory documented Abdy’s possessions at both his country ‘mantion’ in Leytonstone and his city residence, where his business was based, on Lime Street. It valued his ‘goods’ at Leytonstone at nearly 335 pounds (‘334li 18s 4d’). As for his Lime Street residence, it appraised ‘the Goods & Merchandize’ there at more than six thousand pounds (‘6071: 9: 3’). Abdy was evidently a very wealthy man by the time that he died.

Much of the value of Abdy’s estate lay in his ‘Merchandize’ (principally textiles such as satin, cotton, calico, and various kinds of silk). He also, though, owned substantial collections of furniture, glassware, porcelain, jewellery, and plate. Other valuable items that he possessed included Turkish and Persian carpets and quilts from Gujarat—all almost certainly acquired in his capacity as a merchant.

As well as his goods and merchandise, the inventory also lists Abdy’s many books. These were spread across both his houses. At Leytonstone, they included copies of Pliny’s Natural History and Richard Knolles’s Generall Historie of the Turkes (first published in 1603). The latter was just the sort of book that a merchant with Levantine interests would have wanted to own.

At Lime Street, Abdy’s books included devotional material (‘4 Bibles, 1 Service booke and psalme booke’) and books in various bibliographical formats and bindings (‘4 large Folo bookes 9 in a small folo: 7 in quarto: 2 in ottavo: with divers others bound in parchment’). They also included the most distinctive items in his library: ‘17 Italian bookes of severall sortes’.

Italian was the lingua franca for trade across the eastern Mediterranean in the seventeenth century, and a merchant such as Abdy, who had extensive commercial interests in that geographical area, would undoubtedly have been able to speak and read the language. The ‘17 Italian bookes’ probably included guides to Italian itself and also dictionaries. They also almost certainly included guides to commerce and ‘practical’ mathematics: books such as Giovanni Battista Zucchetta’s Prima parte della arimmetica (1600), an instructional manual written specifically for merchants, and which we know was familiar to contemporary English readers.

Abdy’s library contained more literary fare too. We know this because at least two of his ‘Italian bookes’ have survived. Those books are an English translation of Giovanni Boccacio’s Decameron (1620), and a 1625 edition of Boccacio’s The Modell of Wit, Mirth, Eloquence and Conversation. Both books are now in the library of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon: they can be identified as Abdy’s copies because of the armorial stamps on their bindings and bookplates on their front pastedowns.

It seems likely, moreover, that they were not the only ones with these marks. The tantalizing possibility, therefore, remains that more of Abdy’s ‘Italian bookes’ may be discovered in the future.

A Merchant Book (and Plant) Collector from Stepney

Robert Stanier (d. 1673), my second example, was a resident of Bethnal Green in the parish of Stepney, and the descendant of a German family from Cologne. The Stanier family traded with Flanders, Amsterdam, and Spain, and they also had significant commercial interests in the eastern Mediterranean.

We know about Stanier’s book collecting thanks to a ‘Schedule’, or codicil, that he added to his will on 6 October 1673, just a few weeks before he died. That will (DL/C/B/008/MS09172/063, will number 177) survives amongst the records of the Commissary Court of London, held at LMA. It was then proved on 2 December 1673, meaning that Stanier must have died at some point between early October and early December that year.

Stanier left the bulk of his collection to his nephew Samuel, along with all his ‘Deeds and Evidences’, his pictures and statues, his tapestries, his house clock, a dozen silver forks, the jack and fire-irons from his kitchen, and a fine walnut tree cabinet from his dining-room. The ‘Schedule’ sets out the bequest of his books:

'To my nephew Samuell Stanier … Dr Donnes Sermons, Some of my History Books namely Sir Walter Raleighs, Plutarchs Lives, Josephus, Iohn Speeds History and Mapps, H: C: de Avila, John de Serres, Phillip Commines, Pierre Mathew of Lewis the Eleaventh, Guicchiardine, Cornelius Tacitus, Nero Cæsar, Fines Morisons Itinerarie, Suetonius, Samuell Daniell, Sir Francis Bacon of Henry the Seaventh, The Earle of Cherbury of Henry the Eighth, Linschotens Voyages, Vincent Le Blanck, a Collection of Histories beginninge with the life of Almansor, another beginninge with Sir Hen: Blounts Voyage into the Levant, another beginning with the Conquest of West India by Ferdinando Cortez, The Life of Henry the great by the Bishop of Rodez, The life of Pireskius by Gassendus, The life of Father Paul the Venetian, The life of Mahomet by Sir Walter Raleigh, Exemplary Novels by Michaell de Cervantes, The Memoires of Margaret Queene of Navarre.'

Stanier’s library clearly included devotional material, histories, geographies, travel works, itineraries, life-writing, and even some early novels. Evidently, it also included works by many of the most prominent authors of the day. Furthermore, like Abdy’s library, it seems to have been a collection created for both edification and use; a collection formed with its owner’s day-to-day commercial concerns in mind and out of more humanistic interests in letters, literature, and history.

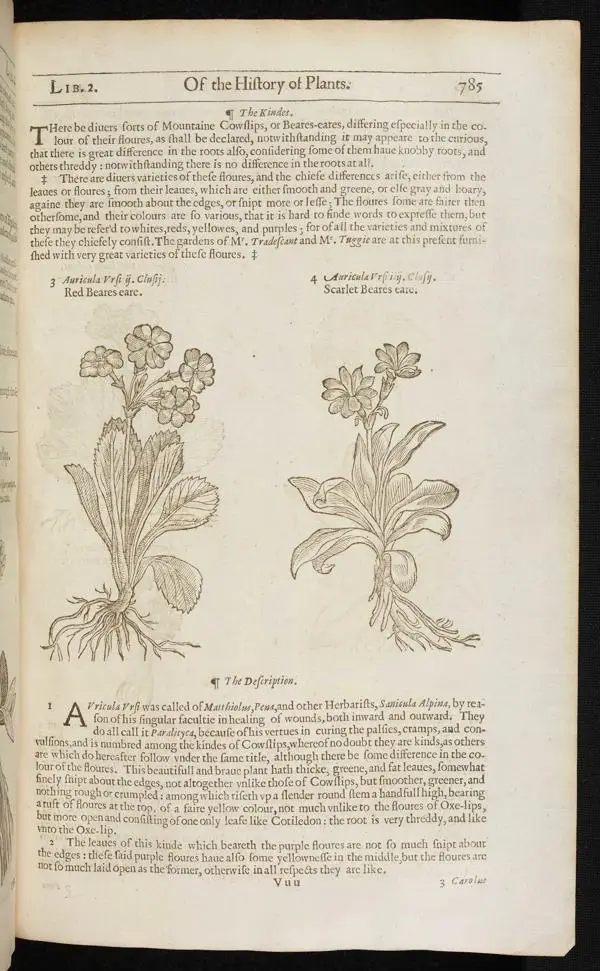

Books were not the only things that Stanier collected. From the ‘Schedule’, we learn that he also collected plants. He seems, in particular, to have had a sizeable collection of auriculas, a type of primula (also known as bear’s ear) popular with plant collectors and flower fanciers at the time. He left these to his friend and fellow merchant William Whitmore of Balmes in Hackney, inviting him in his will to choose ‘such and soe many of my potts of Auriculas as he shall please’.

As it happens, Stanier was also not the only member of his family to collect books. His older brother James, another merchant, also owned a collection, which he bequeathed to his two sons ‘to be devided betweene’ them (The National Archives (TNA), PROB 11/312/556, fols 317v–318r).

The Clitherow Manuscripts

My final example, the Clitherows, came to prominence in the early seventeenth century as merchants in the City of London and members of the Ironmongers’ Company. Evidence of their book collecting comes from a series of documents in the family archive. For more than 300 years that archive was housed at Boston Manor in Brentford, the Jacobean manor house that from 1670 was their principal seat. In 1976, however, the contents of the Clitherow archive were moved to LMA, where they now take up more than twenty-five metres of shelving and include no fewer than 784 separate items.

Amongst the collection’s varied records there are two vellum-bound seventeenth-century literary manuscripts. These are an anthology (ACC/1360/528) from the 1630s and a hitherto unidentified play-text (ACC/1360/529) also from the 1630s. Both appear to have belonged originally to Christopher Clitherow (c.1578–1641), Master of the Ironmongers’ Company in 1618 and again in 1624, Deputy-Governor and Governor of the East India Company in 1624 and 1638, Lord Mayor of London in 1635–36, and also Master of the Eastland Company in the 1630s.

Both manuscripts deserve to be much more widely known than they currently are. Both contain unique literary material and both warrant further research. The anthology contains copies of poems by many of the seventeenth-century’s most popular poets, including John Donne, Joshua Sylvester, Richard Corbett, William Strode, Henry King, William Browne, Ben Jonson, Thomas Carew, William Davenant, and Robert Herrick. It also contains a unique piece: a poem titled ‘D: M: D:ni: Io: Donne S: Th: Doctoris:’, a previously unknown (and accomplished) sixty-six line elegy on the death of John Donne by the scholar and courtier Sir Francis Kynaston.

The play-text is, if anything, even more intriguing. Titled ‘The Destruction of Hierusalem, a Tragedie’, this play is a gruesome dramatization in rhyming couplets of the siege of Jerusalem in 587 BC by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. Until now, the source of the play has remained unknown and various suggestions have been proposed for its author. I, however, have recently been able to establish that it is an English translation of the French Jesuit Nicolas Caussin’s tragedy Solyma (1620).

Why a London merchant should have ended up owning an English translation of a Neo-Latin play about a Jewish king by a French Jesuit playwright is still an open question. However, one answer may lie in the Clitherows’ well-known interest in education: Jesuit drama was fundamentally educational in terms of both its subject matter and its performance contexts. Another answer may be the family’s confessional identity: the Clitherows were not Catholics, but they were high Anglicans with probable Arminian sympathies.

The two manuscripts formed part of a larger family library at Boston Manor. That library probably originated with Christopher Clitherow and was then significantly expanded by his son James (1618–82). His account-books (ACC/1360/437, ACC/1360/439) contain regular records of purchases of books. Subsequent generations of the family then added to the library. By the early twentieth century, when an inventory of the house (ACC/1360/525) was prepared, the collection numbered more than 2,000 books.

Conclusion

When we think of literary culture and libraries in the early modern world, we rarely think of merchants. Figures such as Christopher and James Clitherow, Robert and James Stanier, and Anthony Abdy - and documents such as the inventories, account-books, and wills described here - suggest that we should start doing so.

List of References

In LMA:

- CLC/509/MSS05100–05110 (Sir William Turner’s account-books)

- CLC/B/227/MS35025 (Daniel Harvey’s ‘Italian’ ledger)

- CLC/B/013/MSS23953–23955 (Richard Archedale’s books)

- CLC/521/MS03760 (‘Inventories of the Goods & Chattells belonging vnto ye right worll: Anthonie Abdie Late Alderman of the Cittie of London, which were found & valued in his houses at Laytonstone in Essex and in Limestreete London Nouember 18th 1640’)

- DL/C/B/008/MS09172/063, will number 177 (Robert Stanier’s will)

- ACC/1360/528 (the Clitherow anthology)

- ACC/1360/529 (‘The Destruction of Hierusalem, a Tragedie’)

- ACC/1360/437 (‘A Booke of seuerall Accos: kept by mee James Clitherow of money recd: & pd: for diuers persons. B. Begunne Anno: 1652.’)

- ACC/1360/439 (‘A Booke of seuerall Accos: kept by mee James Clitherow of money Recd & Paide for diuers Persons. C. Begunne Anno: 1666.’)

- ACC/1360/525 (‘Inventory of the Contents of Boston House, Brentford’)

In the National Archives:

- PROB 11/312/556, fols 317v–318r (James Stanier’s will)

About the Author

Dr Angus Vine is Associate Professor in Early Modern Literature at the University of Stirling. He currently holds a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship (2021–22) and is writing a book titled Lives and Ledgers: Early Modern Merchants and Books. The stories introduced here are told at greater length in that book. LMA is a partner on the project.