Unforgotten Lives - Rights

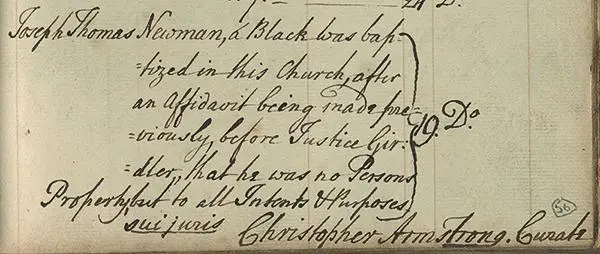

A significant number of people of colour identified in the Switching the Lens dataset were brought to London in 1600s and 1700s as enslaved people from the Caribbean and Americas to work in domestic households. Their ‘status’ upon reaching England was hotly debated. Judgements by John Holt, Lord Chief Justice in cases in 1696 and 1701 concluded that slavery did not exist in England and that formerly enslaved people could not be regarded so while in England. Several court cases in the eighteenth century appeared to uphold this principle, most famously the case of James Somerset in 1772. The idea of baptism was linked to this notion and to be baptised increasingly was considered to confer free status.

The lives of Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho who became prominent public figures within London society appear to show that restrictions could be navigated. But the reality was often different for many of the people we encounter in the records. Legal rulings did not prevent rights being denied consistently because of ‘race’. Instances of discrimination, violence, kidnappings, false imprisonment and forced deportations all point to the fragility of the position of many people of colour in London during this period as the following examples show.

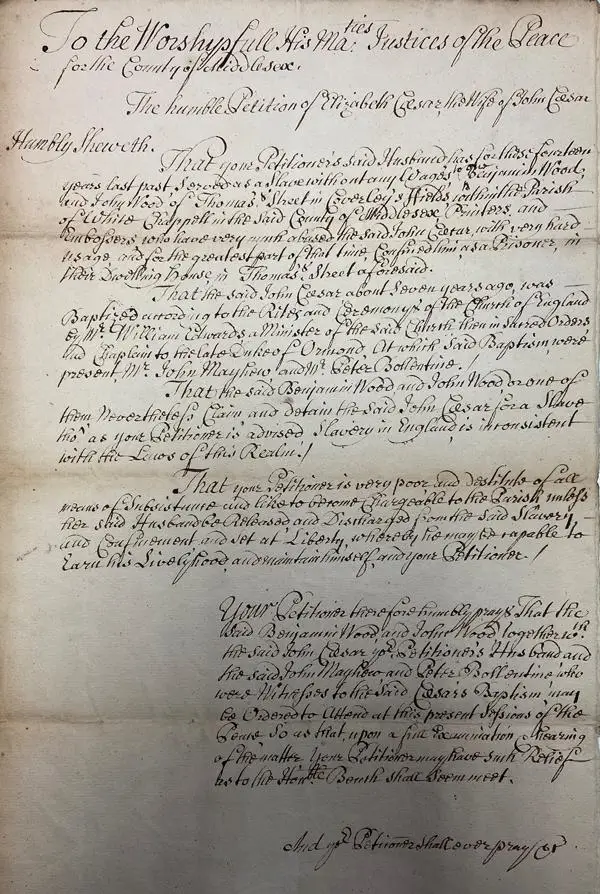

In September 1717 Elizabeth Caesar petitions the Middlesex Sessions court on behalf of her husband John. She claims that John has been forced to work as “a slave without any wages” for the past 14 years for Benjamin and John Wood, printers and embossers of Thomas Street, Whitechapel. Elizabeth tells the court that John has been “much abused” and in effect “confined as a prisoner” at the Woods’ property. Elizabeth is petitioning the court because she is “very poor and destitute” and asks that her husband be released from “the said slavery and confinement and set at liberty” to earn his livelihood.

Elizabeth’s argument rests upon two facts: firstly, that her husband has been baptised seven years before in the Church of England and secondly, that “slavery in England is inconsistent with the laws of this realm”.

At no point do the court records describe John as a person of colour and the circumstances of the case give no additional context, but Elizabeth’s linking of the act of baptism with the incompatibility of enslavement suggest that this is likely. The court finds in favour of Elizabeth and John, agrees that he deserves to have “reasonable wages” and that he “ought not to be used as a slave”.