Unforgotten Lives: Uncovering the identity of Joshua Reynolds’ servant

Sir Joshua Reynolds, the portrait painter and founder of the Royal Academy, employed a Black servant at his house at 47 Leicester Square in the 1760s. This was not uncommon in London’s elite households. For instance, Reynolds’ close friend Dr Samuel Johnson employed the Jamaican born Francis Barber and Ottobah Cugoano worked for Richard Cosway, artist and fellow Royal Academician in 1780s.

Barber and Cugoano are relatively well documented, but Reynolds’ servant remains more of a mystery. We learn about him from James Northcote a fellow artist who published the first biography of Reynolds in 1813. Northcote tells us that he was from Antigua, was formerly enslaved there by Colonel Valentine Morris before being brought to England after 1743; and interestingly, that he appears in several of Reynolds’ paintings, specifically the portrait of the Marquis of Granby.

But Northcote fails to tell us this servant’s name. Perhaps he did not know it or perhaps he did not consider the information important enough to include. Forever unnamed, he is consigned to the very margins of history and the Unforgotten Lives exhibition team at LMA took up the challenge of exploring further.

The prospect of putting a name to a face some 200 years later might seem unlikely, but Northcote provides a major clue in an anecdote from the late 1760s:

'Sir Joshua, as is his usual custom, looked over the daily morning paper at his breakfast time; and on one of those perusals, while reading an account of the Old Bailey Sessions, to his great astonishment, saw that a prisoner had been tried and condemned to death for a robbery committed on the person of one of his servants…'

According to Northcote, Reynolds immediately summoned his servant to demand an explanation. The story emerged that, following a dinner party at the house, this servant had been told to accompany one of the guests, Mrs Anna Williams, to her lodgings in Bolt Court, off Fleet Street in a Hackney carriage. Having dropped the lady off, the servant bumped into acquaintances on the way home and when he eventually returned, he found the Reynolds house locked up for the night. Forced to find shelter in a watch-house, he fell asleep there and was robbed.

The records of trials heard at the Old Bailey in 1700s are held at London Metropolitan Archives. The contemporary journalistic transcripts of these court cases, known as the Old Bailey Sessions Papers, have been digitised and are fully searchable online.

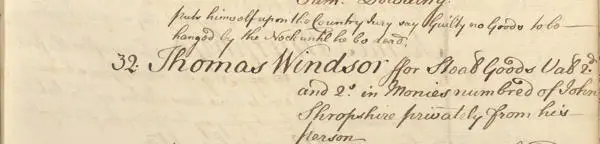

Checking these trials for possible matches, one case stands out. That of John Shropshire who comes to the court on 21 October 1767 to prosecute Thomas Windsor, accused of robbing him. Could John Shropshire be Reynolds’ servant?

John begins his witness statement:

“I was sent to see a lady home to Fleet-street, with a hackney coachman. When we had set the lady down, the coachman and I had a pot of beer; it was rather too late to go home; I went to a night-cellar, and when I was sleeping there… I found my pocket was cut, and two shillings taken out of it”

The defendant in the case is Thomas Windsor. Both he and Shropshire are described in the court records as ‘Black’ (though in several newspaper reports Windsor is described as ‘East Indian’). Windsor tells us that he is a servant with Esquire Spooner of Cavendish Square. This is possibly Charles Spooner of Harley Street, an enslaver with links to Jamaica, Antigua and St Kitts. Sadly, John Shropshire makes no mention of his employer.

The trial evidence states that Shropshire had been 'drinking all night, before he came into our company; he was very merry, and in liquor' and that the crime occurs in a late-night drinking establishment called the Red Lion in Piccadilly.

These facts run contrary to Northcote’s account but perhaps this is not surprising. Northcote was not present when the story unfolded in the Reynolds household. He is retelling a story second hand after a period of some 40 years. His source is presumably Reynolds himself (Northcote became his pupil in 1771) and Reynolds might never have known the full version of events. He had only the newspaper report and his servant’s account to go on. We have identified three newspaper reports of the case, but none mention the fact that Shropshire was drunk, and Reynolds’ servant probably downplayed this aspect for fear of recrimination (with, it turns out, good reason, as we’ll see below).

Thomas Windsor is found guilty and sentenced to death, but we subsequently find that the sentence is commuted to transportation some months later. Northcote’s version concurs with this. In fact, he goes further, explaining that Reynolds is so outraged that a man has been sentenced to death upon the actions of his servant, he personally petitions the court for clemency. He also orders his servant to take food to the prisoner every day until he is shipped to North America. Both a humiliating act of punishment for the servant and an act of charity towards the prisoner.

So, we rest our case. You can read a full transcript of the trial here and you the jurors must decide! But either way, the court record is fascinating. It’s an insight into London night life and a salutary reminder of the perils of late-night drinking in Georgian London. It also shows how sessions papers highlight the lives of everyday Londoners in a way other records cannot, giving voice to those at the margins of society. Although these are journalistic accounts of trials, their question-and-answer format provides a tantalising chance to hear 18th century Londoners ‘speak’.

Finally, that both defendant and prosecutor in this case are people of colour is clear evidence of presence in Georgian London. When we consider that another case heard on the very same day involves Thomas James, described as a ‘Lascar’ from Bengal, this snapshot of London society presents a diversity which is hard to ignore.