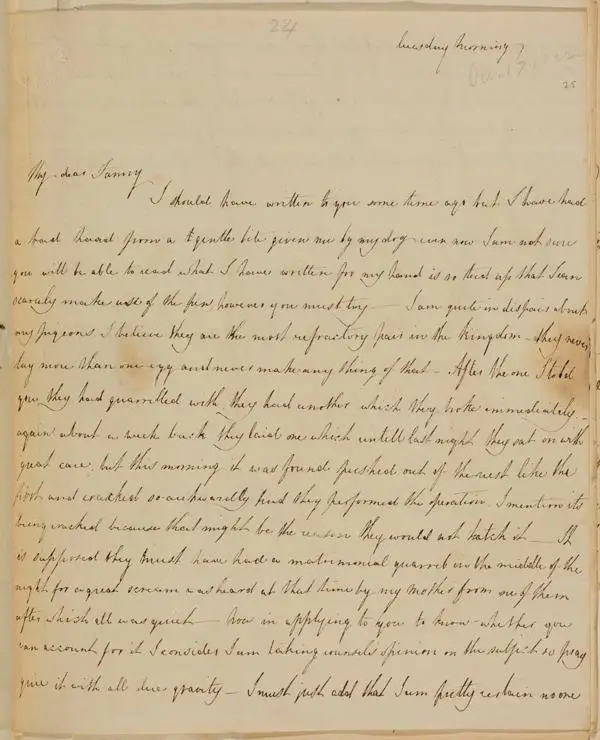

Fanny Brawne's letter to Fanny Keats, 15 October 1822

Before he parted from Fanny Brawne and left Wentworth Place, Keats asked her to write to his sister, Fanny Keats. They began a correspondence of 31 letters over a four-year period.

Keats House are publishing the letters from Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats online on the 200th anniversary of them being written. This project reveals the lives of two women living in London in the 1820s. See ‘Related links’ to read other letters. 'The journey of the letters' tells the story of how they came to be in the Keats House collection.

The letter

After Fanny Brawne’s last two letters, both written at the beginning of September, there was a gap of over a month before she wrote again. The reason for her silence was that the Brawne family’s dog, Carlo, had bitten her on the hand, and the bandage made it difficult to write. The news later reached Charles Brown in Italy after Charles Wentworth Dilke wrote to him, and Brown then passed on the news to Joseph Severn.

Fanny returns in her letter to news about her pigeons, which had featured in previous letters. She ends by giving her opinion of a book she had been reading again, ‘Gil Blas’, and she compares it with ‘Don Quixote’.

Tuesday Morning

My dear Fanny

I should have written to you some time ago but I have had a bad hand from a gentle bite given me by my dog, even now I am not sure you will be able to read what I have written for my hand is so tied up that I can scarcely make use of the pen, however you must try – I am quite in despair about my pigeons, I believe they are the most refractory pair in the kingdom – they never lay more than one egg and never make anything of that – after the one I told you they had quarrelled with, they had another which they broke immediately, – again about a week back they laid one which untill last night they sat on with great care, but this morning it was found pushed out of the nest like the first and cracked so awkwardly had they performed the operation. I mention its being cracked because that might be the reason they would not hatch it – It is supposed they must have had a matrimonial quarrel in the middle of the night for a great scream was heard at that time by my Mother from one of them after which all was quiet – Now in applying to you to know whether you can account for it I consider I am taking counsel’s opinion on the subject so pray give it with all due gravity – I must just add that I am pretty certain no one had in any way touched or molested them – in consequence of my hand I have fed them this fortnight or more, but the housemaid who has done them for me, is by no means a person to touch forbidden things particularly as she knew the consequences – and we only knew they had an egg by their constantly setting, – so much for them. I will try them in confinement a little longer, after that if they do no better they shall be left to themselves – Mrs Dilke is returned and next time I call to see you I shall bring her if I know of it in time. Mr Brown is safely arrived at Pisa and in spite of his vow has made an acquaintance with Lord Byron, he liked him very much – I have been reading Gil Blas again and I like it as well as ever, but I do not wonder at your disappointment for it is so totally different from Don Quixote and wants the romantic parts so much besides showing so much of the worst part of the world that to many people it must be a very disagreable book – I remember hating it at first – I will not write any longer for fear of straining my hand

Yours very affectionately

Frances Brawne

Postmark: 12 o’clock, Oc. 15. 1822.

Address: For Miss Keats / Richard Abbeys Esq. / Walthamstow.

The Brawne family’s dog Carlo

Carlo appears in Keats’s letters as ‘a devil of a fellow’. In February 1820 he wrote to his sister, describing what he can see from the parlour in Wentworth Place where he had been confined after his first haemorrhage:

‘I mus’n’t forget the two old maiden Ladies in well walk who have a Lap dog between them, that they are very anxious about. It is a corpulent Little Beast whom it is necessary to coax along with an ivory-tipped cane. Carlo our Neighbour Mrs Brawne’s dog and it meet sometimes. Lappy thinks Carlo a devil of a fellow and so do his Mistresses. Well they may – he would sweep ’em all down at a run; all for the Joke of it.’

Unfortunately, in her very next letter to Fanny Keats, written on 29 October 1822, Fanny Brawne reported that Carlo had died:

‘Thank you for your enquiries about my hand, it would not have been so bad but the dog was ill at the time he did it and the doctor thought it better to provide against the consequences that always may follow a dog’s bite. Carlo was not the least in the wrong it was entirely my fault, he, poor fellow is since dead from something he had swallowed, but I shall have quite a long story to tell you about it when we meet.’

The news about the bite eventually reached Charles Brown and Joseph Severn in Italy after Charles Wentworth Dilke wrote to Charles Brown. In 1822 Charles Brown moved out of his half of Wentworth Place, intending to live in Italy with his son Carlino and write for Leigh Hunt's journal 'The Liberal'. He arrived in Pisa on 31 August 1822. In Italy he met Lord Byron and Edward Trelawny, and Brown later introduced Joseph Severn to Byron. Severn first met Trelawny in 1823. Brown wrote to Severn on 7 November 1822:

‘You will be distressed to hear that Miss Brawne has been dreadfully bitten on the hand by a large dog. Dilke has sent me the most minute particulars of this accident, which I need not copy, as I can assure you they satisfy me tolerably well that the dog was not mad, – as well as if you read them yourself, perhaps better. In the mean time, the chance of his having been mad disturbs me not a little. Good God! the worst that may happen is frightful to think of.’

Severn replied on 7 December 1822, beginning his letter ‘Unlucky dog’, and adding ‘I am all anxiety to know about poor Miss Brawn pray tell me this – if you have more accounts –’

Brown replied on 20 December 1822:

‘Miss Brawne, by the last news, was recovered so far that the wounds were all healed without any poisonous symptoms. I am under no apprehension about her. I expect a letter from her daily.’

If Fanny Brawne did write back to Charles Brown, the letter has not survived.