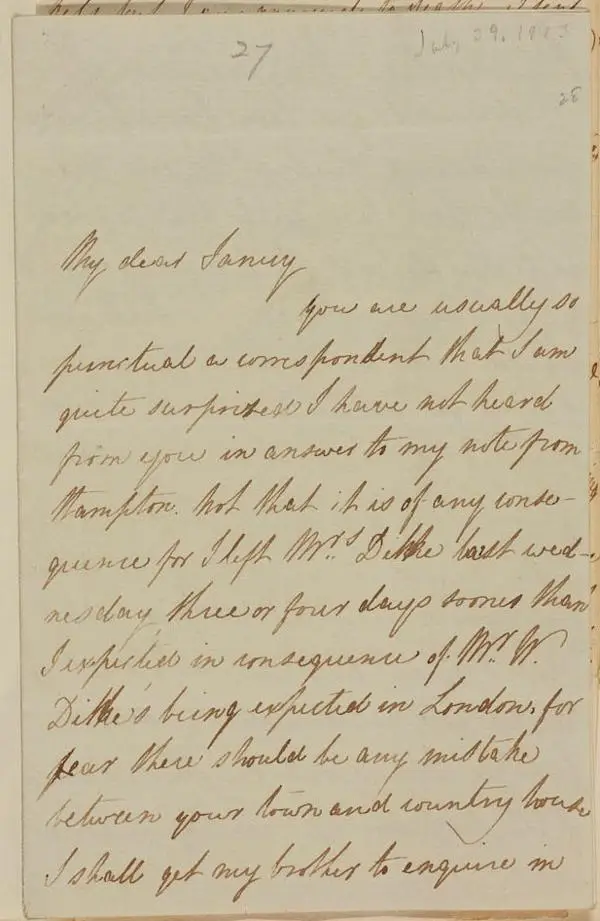

Fanny Brawne's letter to Fanny Keats, Monday 28 July 1823

Before he parted from Fanny Brawne and left Wentworth Place, Keats asked her to write to his sister, Fanny Keats. They began a correspondence of 31 letters over a four-year period.

Keats House are publishing the letters from Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats online on the 200th anniversary of them being written. This project reveals the lives of two women living in London in the 1820s. See ‘Related links’ to read other letters. 'The journey of the letters' tells the story of how they came to be in the Keats House collection.

The letter

In her last letter, written some time in the first half of 1823, Fanny Brawne said that she had put together a parcel of books and magazines to send to Fanny Keats for her to read. In this letter we find out that Fanny Brawne owns ‘very few’ books. Instead, she visits a circulating library, situated nearby in the High Street. Fanny mentioned previously in her letter of 3 February 1822, that her neighbour Charles Brown also used the library.

The copy of ‘Spencer’ that she mentions was given to her by Keats. Fanny Keats kept it but lost it later when she was travelling in Germany. As well as the bound copies of the ‘London Magazine’ that were in the parcel, Fanny Brawne has also been sending her other issues of magazines after she has read them, but she has lost track of which ones, as she has been away from home ‘so much during the last three or four months’.

One of the magazines that we know Fanny Keats did read, was the London ‘Literary Chronicle’. In December 1821 the magazine reprinted a nearly complete version of Shelley’s poem ‘Adonais’, and Fanny Keats later copied it into a letter she sent to her brother George in 1826.

We know a few of the other books that the Brawnes owned. Fanny Brawne mentions in this letter that they have an edition of Shakespeare in more than one volume, and the auction of Mrs Brawne’s possessions after her death included ‘a small collection of books, including Pope, Milton, Johnson, and Pindar’s works, &c.’

Fanny Brawne writes that she has recently visited Hampton again, and also Hampton Court, ‘my old favourite’. In March 1822 she had hoped to take Fanny Keats there, writing that ‘I would give the world if you could go with me the palace is so beautiful’ but she knew that this could only happen if Fanny Keats’s guardian Richard Abbey released her from her ‘present slavery’. In this letter, Fanny Brawne hopes that she will be able to do this next year, after Fanny Keats comes of age on 3 June 1824. Fanny Keats continued to believe, regardless of the evidence of the baptismal register and of what Fanny Brawne says here, that she would come of age in June 1825.

My dear Fanny

You are usually so punctual a correspondent that I am quite surprised I have not heard from you in answer to my note from Hampton. Not that it is of any consequence for I left Mrs Dilke last wednesday, three or four days sooner than I expected in consequence of Mr W. Dilke’s being expected in London, for fear there should be any mistake between your town and country house I shall get my brother to enquire in Pancras lane, for your present residence. I have been from home so much during the last three or four months that I am quite bewildered as to the dates of the last magazines &c. you have received. I wish you would write me word whether you would like all the papers you have missed and what the last was you received. If you have finished Spencer or any of the bound magazines I will send you some more. I have so few books that I cannot lend you all I wish you to read, as I am obliged to get them from the library, but the other volumes of Shakespeare you can have when ever you like – I passed a pleasant time at Hampton and saw my old favorite Hampton Court several times. I hope to take you there yet, only a twelvemonth, Fanny, from last June. You had better begin Mrs Abbey’s veil soon or she will never have it, bye the bye I have learnt some stitches for that sort of work and if you like I will show them to you. I hope to see you soon,

and remain, yours very affectionately,

Frances Brawne

Monday –

Postmark: Lombard St. Ev. Jy. 29. 1823.

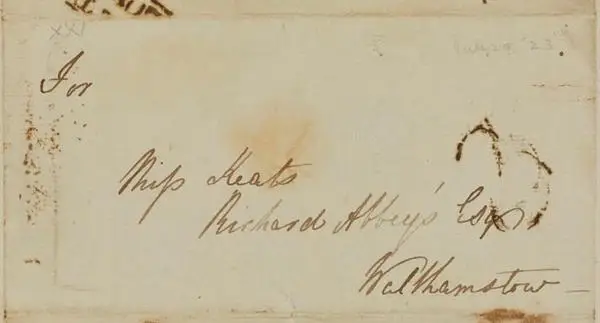

Address: For / Miss Keats / Richard Abbey’s Esq. / Walthamstow.

Further information

The Literary Chronicle, 1 Dec 1821

Read the review of Shelley’s ‘Adonais’ (Internet Archive)

Hampton Court

The Hampton Court Guide, 1817 (Internet Archive)

Hampton Court during the reign of George IV (Internet Archive)

Contemporary images of Hampton and Hampton Court (London Picture Archive)

Joseph Severn, Charles Brown and Keats’s gravestone

In 1823, Severn and Brown, both living in Italy, were still discussing the erection of a gravestone for Keats. The burial of Shelley’s ashes had taken up much of Severn’s time, but in January he wrote to Brown:

‘My next sad office is to place poor Keats Grave Stone which is not yet done – I hope this week it will be finished – I shall put some Evergreens round it – of course it is the Old Ground – I was going to make a proposition to you – […] I am going to ask your advice about a little Monument to Keats – more worthy him than ours – to be placed (if it was thought better) in Hampstead Church – What gave [me] this Idea was the applications of several gentlemen to subscribe 20 Guineas &c for this purpose – I have no doubt it might be done – The Subject of a Basso-relievo was this which I thought – “Our Keats sitting – habited in a simple Greek Costume – he has half strung his Lyre – when the Fates seize him – One arrests his Arm – another cuts the thread – and the third pronounces his Fate”’

Brown replied in February:

‘There is one subject in your letter that has employed my consideration, […] I mean the erecting of a monument to Keats’s memory in England. In one word, I cannot but disapprove of it. The fact is this: his fame is not sufficiently general; with the few and the best judges it stands high, but his name is unknown to the multitude. Therefore I think that prior to his name being somewhat more celebrated, a monument to his memory might even retard it, and it might provoke ill-nature, and (shall I say it?) ridicule. When I quitted England his works were still unsaleable. For that cruel word ridicule I must explain myself. There appeared, some time after his death, in one of the Government newspapers, an article scoffing at him and joking at his death. I did not read it, I could not, but I heard of it, and it put me in a fortnight’s irritation. In prudence we ought to wait awhile. First, let his merit be undoubted. Let it not be said that not only bad men have costly tombs with flattering inscriptions, but that nowadays bad poets have the like. This will be as unpleasant as irksome, as discordant for you to read as it is for me to write; but I must tell you the truth, his name is yet scarce anything in England; it becomes, and will become, more enobled every day, while a monument might throw that happy time back. Ten years hence, to my mind, will be time enough. You, in your affection for him, think nothing can be done too much. Alas! I, knowing the wretched literary world, think otherwise. Yet still all this is but one man’s opinion, and one as likely to err as yourself, and from the same motive, though our opinions are contrary.’

In June Severn wrote to William Haslam:

‘I have just put up the Tomb to poor Keats – it has cost me 16£ - but Brown insists on paying half […] Our Keats Tomb is simply this – a Greek Lyre in Basso relieve – with only half the Strings – to show his Classical Genius cut off by death before its maturity – the Inscription is this “This Grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet – who on his death-bed – in the bitterness of his heart – at the malicious power of his enemies – desired these words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone”

“Here lies one whose name was writ in Water”’

According to Sir Charles Dilke, Severn paid the bill and refused Brown’s offer.