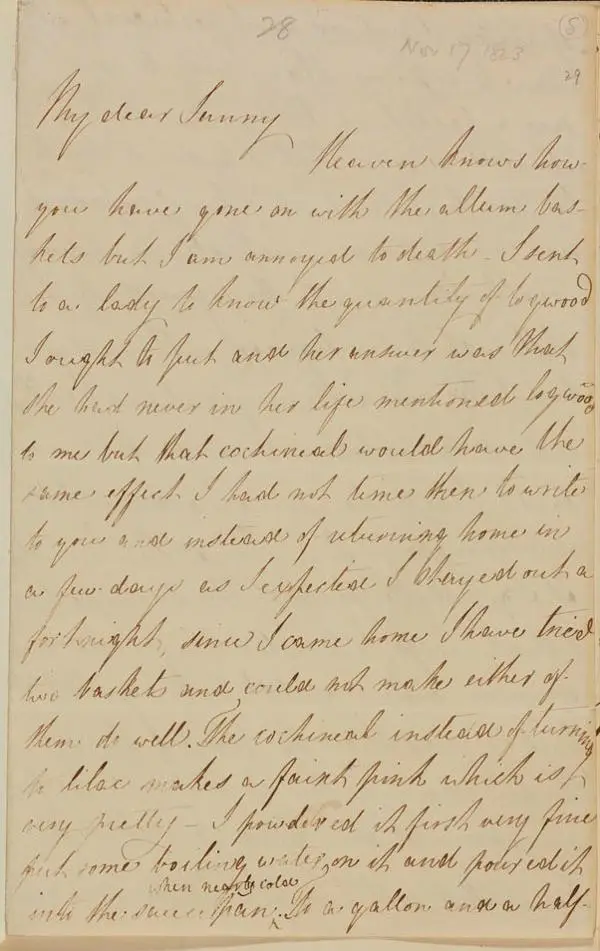

Fanny Brawne's letter to Fanny Keats, Sunday 16 November 1823

Before he parted from Fanny Brawne and left Wentworth Place, Keats asked her to write to his sister, Fanny Keats. They began a correspondence of 31 letters over a four-year period.

Keats House are publishing the letters from Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats online on the 200th anniversary of them being written. This project reveals the lives of two women living in London in the 1820s. See ‘Related links’ to read other letters. 'The journey of the letters' tells the story of how they came to be in the Keats House collection.

The letter

In this letter we find out that both Fanny Brawne and Fanny Keats have been making and decorating alum (or allum) baskets. An alum basket was 'a small decorative wire basket covered in alum crystals by being dipped in a saturated solution of alum to give a sparkling effect’ (Wiktionary). She also mentions Logwood, which was a vegetable dyestuff used for fabrics, and Cochineal, a red dye.

Fanny Brawne mentions a few of her friends and acquaintances – she reports that she has been to a ‘quadrille party’ at the Davenports’ house in Hampstead, and that she has quarrelled with Valentine Llanos (‘Mr Guiterez’, who later married Fanny Keats). She also gives her opinion of Miss Lancaster and has news that Miss Rowcroft is departing for South America.

My dear Fanny

Heaven knows how you have gone on with the allum baskets but I am annoyed to death – I sent to a lady to know the quantity of logwood I ought to put and her answer was that she had never in her life mentioned logwood to me but that cochineal would have the same effect. I had not time then to write to you and instead of returning home in a few days as I expected I stayed out a fortnight; since I came home I have tried two baskets and could not make either of them do well. The cochineal instead of turning to lilac makes a faint pink which is very pretty – I powdered it first very fine put some boiling water on it and poured it into a saucepan when nearly cold. To a gallon and a half of water I put as much cochineal as came to a penny. After I wrote to you I saw a basket at Mrs Dilkes which I admired so much that it induced me to try my luck, instead of being crossed, it was entirely covered with allum and very faintly coloured with the logwood, if you still wish to try logwood with yours you had better mix certain quantities together and see how it looks when dry – But no doubt I shall see you soon and can tell you more about it – I met the Lancasters at a quadrille party at the Davenports – I think Miss Lancaster plain and very common and ungenteel looking. Mr Guiterez was there, the beau of the room – He has been here this morning and I expect him again tonight – Would you believe it I quarrelled with him but I hope it is now made up – for the defence of my character, I must mention that he was quite in the wrong – I don’t know whether I mentioned that Miss Rowcroft is going to South America immediately

I remain my dear Girl

Yours very affectionately

Frances Brawne

Sunday evening

Postmark: Nov. 17, 1823.

Address: For Miss Keats / Richard Abbey’s Esq. / Walthamstow.

Further information

Alum baskets

These popular baskets are mentioned in ‘Harry and Lucy Concluded: Being the Last Part of Early Lessons’, Volume 2, by Maria Edgeworth, 1825:

‘Lucy ran down to the hall to see whether the basket was there. And there it was, standing beside her bonnet. The wicker skeleton was no longer visible; every part of it, handle and all, being covered with crystals of alum, apparently perfectly formed. […] Miss Watson suggested, that if Lucy should ever attempt to make such a one, she might put into the solution of alum a little gamboge, which would give to the crystals a pretty yellow tint; or she might mix with it any other colour she preferred.’

Instructions for making the baskets can be found in ‘The Girl's Own Toy-Maker, and Book of Recreation’, by E. and A. Landells, 1860.

‘a quadrille party at the Davenports’

Burrage Davenport and his family lived at No. 2, Church Row, in Hampstead. The house no longer exists. The Davenports appear several times in Keats’s letters. Keats usually spells his name as ‘Burridge’. A drawing of the Davenports’ house appears in Barratt’s ‘Annals of Hampstead’, Volume 1, p. 279.

The Quadrille was a popular dance of the time. Read more about the Quadrille.

Preparations for a quadrille party are described in ‘The Home Book; or, Young Housekeeper’s Assistant’, by ‘A Lady’, 1829, p. 126ff.

Miss Lancaster

The Lancasters lived in Marsh Street (now the High Street), in Walthamstow and so were neighbours of the Abbeys.

‘Mr Guiterez was there’

This would be of great interest to Fanny Keats, as she later married Valentine Maria Llanos y Gutierrez.‘

Miss Rowcroft is going to South America’

According to Joanna Richardson in her biography of Fanny Brawne, ‘Miss Rowcroft announced her intention of going to South America, and was only deterred by inflammation of the lungs. She may have saved herself an untimely end, for her father, [Thomas Rowcroft] who became the British Consul in Peru, was soon shot dead by one of Bolivar’s sentries on the Lima road.’ However, according to the newspaper reports, Miss Rowcroft was present when her father was shot.

Thomas Rowcroft was appointed on 10 October 1823. The Rowcrofts travelled on HMS Cambridge, arriving at Rio de Janeiro on 21 February 1824, before travelling on to Lima. Rowcroft was shot on 4 December 1824 while trying to pass between the Royalist and Patriot lines, and died three days later. He was buried on the island of San Lorenzo in Callao Bay. Bolivar’s forces entered Lima on the day of his death, and Bolivar himself visited Miss Rowcroft to offer his condolences.

The Lancaster, Rowcroft, Goss and Whitehurst families who appear in Fanny Brawne’s letters all seem to have been acquainted with each other, and with Richard Abbey, Fanny Keats’s guardian, through business connections.

There are portraits of Thomas Rowcroft in the National Portrait Gallery, and the Government Art Collection.

Leigh Hunt, Lord Byron, and Keats in 1823

In August 1823, Leigh Hunt published in the ‘Literary Examiner’ the conclusion of his article ‘On the Suburbs of Genoa and the Country about London’. It contained a reminiscence of Keats:

'All this reminds me but too painfully of another and greater poet, a lover of Hampstead. […] The road that runs over the heath between [the village of North End] and the Vale of Health is a remnant of the old Roman road or Watling-street [….] On the right of the Highgate-road, pleasant meadows lead over to pleasant places, – Hendon and Finchley; on the left a lane turns off to Highgate and Kentish Town, justly christened Poets’ Lane, both on account of its rural beauty, and the walks here enjoyed by Mr. Coleridge, Mr. Keats, and others. […] The path over the fields to Highgate, or back again to the Vale of Health or the Heath is quite lovely. […] It was from a house on the eastern part of the heath, that Keats took his departure to Italy. Melancholy as it was, and the more so from his attempt to render it calm and cheerful, it was not the most melancholy circumstance under which I saw him there. – I could not hinder him one day from going to visit the house, in which, though he was himself ill and weak, he attended with such exemplary affection his younger brother that died. Dead almost himself by that time, the circumstance shook him beyond what he expected. The house was in Well Walk. […] It was in that grove [of elms], on the bench next the heath, that he suddenly turned upon me, his eyes, swimming with tears, and told me he was “dying of a broken heart.” He must have been wonderfully excited, to make such a confession; for his spirit was lofty to a degree of pride. […] and when he took his departure for Italy, he had hope, or he would hardly have gone. Even I had hope. My weaker eyes are obliged to break off. He lies under the walls of Rome, not far from the remains of one, who so soon and so abruptly joined him. Finer hearts, or more astonishing faculties, never were broken up, than in those two. To praise any man’s heart by the side of Shelley’s, is alone an extraordinary panegyric.'

In contrast, more books of Lord Byron’s epic, ‘Don Juan’ also appeared in the same month. Byron included his infamous stanza on Keats:

John Keats who was killed off by one critique,

Just as he really promised something great,

If not intelligible – without Greek,

Contrived to talk about the gods of late,

Much as they might have been supposed to speak.

Poor fellow! his was an untoward fate;

’Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle,

Should let itself be snuff’d out by an article.

Leigh Hunt later claimed in his Autobiography to have told Byron ‘the real state of the case’, but that unfortunately Byron’s ‘stroke of wit was not to be given up.’

Keats was not forgotten by his other acquaintances. Charles Brown wrote from Italy to his friend Thomas Richards in October:

‘I have to pass, continually, the house, nay, under the very window, where Keats died. This to me is a stronger memorial of his death than his grave. You ask me for my feelings and observations at his grave; – I saw it, rather from a distance, as the keeper of the ground was absent, with no feeling whatever. A grave never affects me; the living man was a stranger to it, and it only contains a clod like itself. One single circumstance of his life, brought to my mind by a trifle that he loved or hated, affects me always, – but not mournfully, – quite the contrary. I have taught myself to think with pleasure of his having been alive and been my friend’

And Mary Shelley wrote to Leigh Hunt in November 1823, ‘Poor Keats I often think of him now.’