Ostrich feather trade

From fashion accessory to feather duster: the ostrich feather trade in London

'Ostrich feathers were valuable commodities at the beginning of the twentieth century, their value per pound almost equal to that of diamonds' (Sarah Abrevaya Stein)

The delicate elegance of the ostrich feather has traditionally been a symbol for luxurious extravagance. The history of dress has been the history of the elite with non-elite fashions being less well documented. The ostrich feather really took off with the fashionable elite in the eighteenth century and ostriches were heavily hunted. By the nineteenth century, the farming of ostriches allowed farmers to pluck the feathers instead of having to kill the birds. The trade peaked in the late nineteenth century before a decline and crash of the market at the onset of the First World War.

In documents held at London Metropolitan Archives, Charlotte Hopkins has found evidence of the ostrich feather industry in London specifically from the Salaman family papers and references in the Sun Insurance Office records. War inevitably transformed a world of refinement and excess into one of immediate austerity until the 1920s when there was a resurgence of interest in the ostrich feather as a fashion item. London had been a major importer of ostrich feathers largely from South Africa since 1865 (where the bird is a native of the continent) with a thriving industry in the heart of the East End.

Feathers in and out of fashion

The ostrich feather has been an accessory of the aristocracy, Lord Mayors and Royalty. Particularly familiar is the Prince of Wales’ Coat of Arms which consists of three white ostrich feathers encircled by a gold coronet. This originated with Edward the Black Prince who adopted a single ostrich feather to honour the memory of King John of Bohemia who was killed in battle with the Prince’s men.

The feather has not vanished from contemporary fashion. It is a favourite in the fans of the dancers of modern burlesque and accented on the catwalks. Alexander McQueen was a great lover of the feather which was apparent in the hugely popular ‘Savage Beauty’ exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2015. Another exhibition dedicated to the feather, ‘Plumes and Feathers in Fashion’ was held at the Bowes Museum in County Durham.

In the years 1885 and 1913 feathers went out of fashion. James Laver’s law of the trend lifecycle says that items fall in and out of favour and can be appreciated again after a certain period of time has passed. The Report of the Ostrich Feather Commission of 1918 states that 'When the article is out of fashion, the less you mention it and the less you show it, the sooner the fashion revives.' (The National Archives ref: CO 633/104). This absence of presence could, in part, be said to relate to the rise in popularity of the ostrich feather again in the 1920s. Naturally, after the First World War a spirit of carefree exuberance followed with a craving to live life to the full through all the modes of excess that were on offer. This could be achieved by the transformative power of fashion which enabled one to express a sense of freedom through dress.

The ostrich feather trade in the East End

During the nineteenth century ostrich feather manufacturers were concentrated in a one-mile radius from the City of London into the East End. In particular, around the Barbican, Aldersgate, London Wall, Jewin Street, Cripplegate, Bartholomew Close, and the Fenchurch Street area as referred to in Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s comprehensive book on the subject, 'Plumes: Ostrich Feathers, Jews, and a Lost World of Global Commerce'(Yale University Press, 2008) available at Guildhall Library reference S 382:4.

Sun Insurance Office records held at LMA indicate the locations of some of the ostrich feather manufacturers in London in the first part of the nineteenth century. Here is a sample from performing a keyword search in the LMA Collections Catalogue for ‘ostrich insured’:

- CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/426/745490 - Insured: Elias Jessurun, 28 Sun Street Bishopsgate Street without, ostrich feather and flower manufacturer (1803)

- CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/490/991986 - Insured: Phineas Milligen, 51 Church Street Minories, ostrich feather manufacturer (1822)

- CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/501/1026082 - Insured: Joseph Defriez, 3 Houndsditch, ostrich feather manufacturer (1824)

This was a labour intensive industry and a highly lucrative one too. Stein’s book provides a graphic illustration of the movement of trade across the globe. From this we can see that in 1883, £500,000 worth of ostrich feathers were imported into London; in 1912, the value of ostrich feathers imported to London from South Africa, with a similar amount imported back out to France, was £2,000,000.

A high proportion of the workers in this industry were immigrant Jewish women and girls who had experience in the needle trades. Workers suffered poor wages and were often subject to the abuse of their rights by employers. The 1911 census reveals the extent of ostrich feather workers in London around this time. One such worker was Marie Ethel Adams who was 18 years of age and her profession was an ‘Ostrich Feather Curler’ living in Shoreditch. Amongst the ostrich feather workers, the curler was the highest paid. It was their job to turn uneven plumes into the beautifully sculpted feathers that could be sold and incorporated into fashion items. As a result of this highly prized skill they were much in demand and were unlikely to be unemployed.

The Salaman Family

The Salaman family were established in 1863 as ostrich feather manufacturers. Isaac Salaman originally operated out of the ground floor shop at 69 Lamb’s Conduit Street. Stein quotes that the shop was 'visited by the great ladies of fashion who did not hesitate to pay £5 for a single feather.' Myer and Nathan Salaman moved the business to Monkwell Street (around 1864) and then to Falcon Square in 1893.

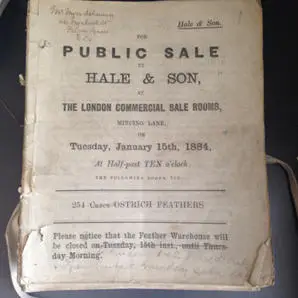

Imported feathers would arrive at the docks and there the Cutler Street warehouses were used for displaying stock to potential buyers. As the trade increased, Myer Salaman relocated the presentation of feathers to the Billiter Street warehouses. The feather importers then handed their plumes to brokers for the monthly auctions held at the London Commercial Sale Rooms situated in Mincing Lane. The Billiter Street Warehouse was an important site in the ostrich feather trade as any items going to auction were put on display there for two days before their sale. By the late 1920s, Isaac Salaman and Company was one of the rare remaining feather merchants in London. However, by 1943 their entire stock of feathers was liquidated.

There were different classes and grades of feathers of varying length and quality and this depended on which part of the ostrich they came from: Whites (highest grade), Feminas, Byocks, Spadones, Boos, Blacks, Drabs, Floss.

Within the Salaman papers held at LMA are reports on the auctions and sales catalogues with the prices realised (CLC/499/MS20508 and CLC/499/MS20509/001-004).

In one such report, S .Figgis and Co. (ostrich feather brokers) analyse the final ostrich feather auction of 1912. 'The quantity catalogued was 115,000 lbs, against 109,000 lbs last sale and 108, 800 lbs in December last year. Owing to the setback that the trade has experienced through the Balkan-Turkish war, a difficult sale was anticipated, and the results are much better than expected.' It goes on to state that of these feathers the feminas sold better than the whites. The 'Blacks were neglected and declined about 20 per cent' and 'drabs - good, long, was 15 per cent cheaper, but other kinds sold steadily, and medium was dearer.'

In 1924, the Board of Directors sold the Monkwell Street property where the business had been for 60 years. 'With feathers no longer in demand as objects of adornment, Salaman and Company now served a rather less glamorous industry: the vast quantities of plumes the company had stored at affiliated warehouses in London were being exported to Germany, France, and the United States to be made into feather dusters.' (Stein, p81).

Note: part of the Salaman collection (collection reference CLC/499) held by LMA is stored offsite and requires 48 hours’ notice for access.

Factors that resulted in the decline of trade

In 1915, Reginald McKenna, the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced a tax of 33 per cent on the import of foreign luxury goods. This severely impacted on the acquisition of ostrich feathers for the London trade. The demand for utilitarian clothing during the First World War and the necessity for women to become part of the workforce contributed further to a shift in the style of hats worn. Sleeker, streamlined options were preferable to the wide-brimmed hats of the early Edwardian era. Not forgetting the development of the motor car which affected the choice in headwear, as larger styles with feather accessories in open-cars were simply not practical.

An article on the 'South African Ostrich Feather Industry' in Journal of the Royal Society of Arts (1924) p.533-534 highlights the value of trade following the War: '…the trade steadily declined until 1918, when the value of feathers exported only reached about £80,000, less than it was 30 years earlier. A comparatively slight revival has taken place since 1918. The exportation of feathers in 1922 amounted to nearly £400,000, but this amount is far below the 1913 figure.'

Another factor was the foundation of the Plumage League in 1885 which was a predecessor of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Its mission had been prompted by the excessive use of birds and feathers for fashion items, as referenced in the Pall Mall Gazette (January 6, 1886), 'After the excess, of the last season or two, it appears that the needed co-operation has at last been obtained.' The Plumage Act of 1921 did not include the prohibition of the importation of ostrich feathers as these birds were farmed for their feathers and did not suffer death. However, the notion of cruelty and harm to other birds meant that to wear anything connected with this species became unfashionable. This in turn had a negative impact on the ostrich feather market as a whole.

The Resurgence of the Ostrich Feather

The British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park in 1924 saw the South African Pavilion display a twenty foot replica of the crest of the Prince of Wales. This was made up of thousands of ostrich feathers. There were even live ostriches on site and feathers could be plucked from them for six shillings. Sourced from 'Birds of Paradise: Plumes and Feathers in Fashion' (LANNOO, 2014).

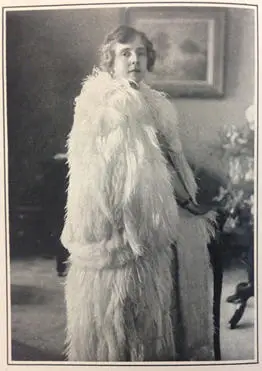

The Illustrated London News in January 1924 presented a photograph of Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone (the last surviving granddaughter of Queen Victoria) in an 'Ostrich feather mantle presented to her by the ostrich farmers of South Africa - she was glad to hear that the ostrich feather industry, which had suffered through the war, was looking up again, and she believed that it had a great future.'