Prometheus Tamed - the history of Fire Insurance Archives at LMA

The wealth of archives held by the City of London has been used over the years for many studies on one of London´s greatest tragedies, the double catastrophe of the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London, 1665-1666. Several studies on the rebuilding, on how the ground plots after the Fire had been surveyed with the help of sophisticated instrumental measurement by Robert Hooke and others, remind us how London itself has a history built on a succession of 'ground zeros'. Even the history of the memory of such events is to be found in the archives as shown by the discussions about the Fire Memorial in the 1670s and 1680s in the Journals of the City of London Corporation’s Court of Common Council.

LMA has a deep relationship with fire history not only in local terms, but also nationally (including charity briefs following the Great Fire concerning the whole country) and in global terms, mostly around the emergence and the spread of the insurance business in London, nationwide and then into the world. Immediately after the Great Fire there was discussion about different schemes for insuring property to protect property owners – including mutual societies, private stock companies relying on capital stock, later continued as joint stock companies, and a scheme led by the City Corporation itself. In 1679-80, a merchant called Augustine Newbold published his own proposal on 'London´s Improvement', which he submitted to the Lord Mayor and Aldermen who discussed it in 1680.

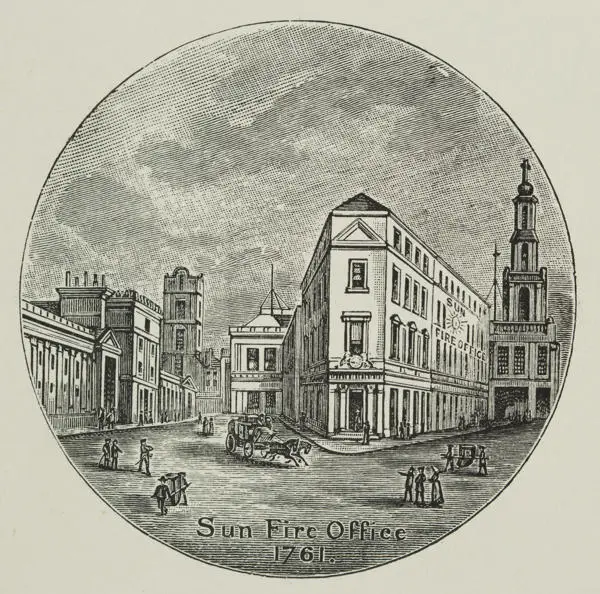

However, neither Newbold´s proposal, nor the City Corporation’s own scheme were successful. It was the private building speculator, inventor, mercantilist and theoretician Nicholas Barbon, who had acquired his wealth through huge building projects in the West End of London, who came up with a successful independent solution, founding the Insurance Office for Houses in 1681 - the first private fire insurance firm in the world – as well as a Land Bank in 1690 rivalling the Bank of England. Barbon is well-known in the history of economic theory, mostly for his Discourse of Trade (1678), and has been recently rediscovered as an early adherent of the concept of real economic growth based on the idea of an alleged ‘infinity´ of resources, 100 years before Adam Smith described it in The Wealth of Nations (1776). Barbon died in 1698 and the Insurance Office was abandoned in 1710, but many other companies appeared soon afterwards. Of these, the Sun Insurance Office founded in 1710 remained the largest, and still exists today as Royal Sun Alliance (RSA).

Barbon´s Insurance Office was the world’s oldest private fire insurance company, but the oldest fire insurance institutions are not to be found in England, but in Germany. From around 1606, the first schemes to merge the Mediterranean maritime principle of premium insurance with early modern territorial administration were conceived in Strasbourg and the idea spread throughout the Holy Roman Empire in the period before the Thirty Years´ War, although without being successfully implemented. The earliest stable state run fire insurance was the Hamburg General Fire Office of 1676, founded around the time when London was still mourning its lost houses and in process of rebuilding, though no direct influence of the London experience on the discussions in Hamburg can be traced. Cities in Germany were burning even more frequently than in England as a comparison of both countries has shown.

The phenomenon of large city fires was an every-day threat in early modern Europe, but in each country they had their own peculiar characteristics. And insurance agents in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had to learn how different the situation was in other continents such as with large cities in India, Japan or with the fast-growing skyscraper cities of the nineteenth century United States of America which witnessed tremendously large city fires, such as in Chicago (1871), Boston (1872), Baltimore (1904) and San Francisco (1906). A further illustration is the ratio between premium income and claims payments which was extremely different in the cities around the globe (very positive: nearly 9% for Bombay, 27% and 42% for Shanghai and Hong Kong respectively, and very risky: 60% for New York, 82% for Hamburg, 87% for Istanbul). The fast-growing industrial cities and an immense wooden metropolis like Istanbul were causing far larger damage than Asian cities.

The LMA holdings, and especially the Sun Insurance Office records (CLC/B/192), give a unique insight into this experience of a ´world burning´ and a world to be insured. Though Germany´s experience in founding insurance institutions was in synchrony with England, more or less alone among the European countries in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, German fire insurance remained state organised and limited always to individual territories, organised by cameralist administrators, in the Holy Roman Empire; they never developed a dynamic of expansion and outreach. In contrast, the English private insurance companies started as early as 1786 to gain global markets, the Phoenix, for example, using a pre-existing network of colonial sugar traders in the West Indies (the Phoenix archives are preserved in Cambridge University Library).

The Sun Insurance Office, already a giant in the UK at that time, expanded later, but with breath-taking speed: between roughly 1835 and 1860 it had founded agencies in all the most important cities around the globe, on every continent, in each of the most important trading cities (the large port cities foremost). Different from other insurers, the Sun Insurance Office was also well organised in terms of monitoring, surveying and recording this expansion. Its officers in the London headquarters copied the incoming information from their agents abroad, sent by way of letters, into so-called Foreign Memorandum Books, and gathered further material themselves. The agents on the spot searched for past and present (proto)statistical data about fire risk, the frequency and extent of burned houses, the climate, fire prevention and other provisions, the legal system, about their competitors, but also about ethnic, cultural and social conditions, circumstances which had to be respected and ‘problems’ to be known, to be calculated for doing business effectively and eventually better than others. They sent hand-drawn sketches, clippings from local newspapers, insurance advertisements in hundreds of global languages, and many precious early photographs from streets, city views, burned 'ground zeros' after large fires that happened when already installed in the city. These 300 plus Foreign Memorandum Books (CLC/B/192/DC/019) are probably unmatched by any other archive in the world (the only other comparable holdings are that of the SwissRe in Zurich, the Phoenix and of the Norwich Union – now Aviva). It is like a - certainly highly selective, self-interested, capitalist and European - view on the world´s urban condition, its fire ecology, and captures the moment of the globalising capitalist economy within the framework of the informal British Empire (and beyond it). German, French, Italian and US insurance companies either did not expand that early in global terms during the nineteenth century, or their company archives are not preserved.

In particular, the records of the Sun Insurance Office offer insight into how insurance ultimately employed important practical and simple mechanisms to effect globalisation during the second half of the nineteenth century, as well as offering an illustration of the perceptual model at work. At first, there is clearly a difference between Western European cities and those perceived as non-Western. The Sun’s Foreign Memorandum Books did not contain maps of Hamburg or New York that meticulously defined insurable and uninsurable zones - though detailed fire insurance maps certainly existed in general for England and the US at that time. The separation between good and bad risks was determined almost solely by differences in building materials. Initially, the foreign agents’ unconscious guiding principle would have been something like the expansion of the Enlightenment’s ‘secure normal society’ across the globe. It was as if the agents wanted to delineate the borders of small normal secure societies transferred out of Europe in each world region on their (real) maps by distinguishing between native and European zones without fully understanding the complexity of the encounter and of the process itself. However, it became apparent that ‘colonial’ classification strategies really had little to do with systematic economic considerations in connection with the large cities across Asia from Istanbul to China and Japan. In India, it was clear that the ‘native town’ was no more vulnerable to fire than the European part of the city and thereby represented an equally good or - due to the relatively low demand for insurance - bad market. It took twenty years for companies to collect the necessary data - namely, their own and others’ loss ratios— that constituted perhaps the only reliable criteria for answering the question of whether engaging in insurance practice was advisable. In China, for example, faced with the complex blending of ethnic boundaries within the Treaty Ports, the Sun abandoned the basic pattern of perception concerning the native/European binary in the face of the evidence, encouraging increasingly fine subdifferentiation in terms of the economic process of premium calculation.

Overall, the way in which the insurance giants of the nineteenth century operated during their global expansion into countries and markets unknown to them is not so different from the early days of fire insurance in London, when Barbon attempted to identify fire statistics and gross damage/loss averages: certainly, Barbon knew London, but his state of knowledge concerning prior and reliable ‘data’ on its fire ecology was quite similar to that of his followers two centuries later in different cities around the world.

Privatdozent Dr habil. Cornel Zwierlein has adapted the above article from his recently published Cornel Zwierlein: Prometheus Tamed. Fire, Security and Modernities, 1400-1800, Leiden/Boston: Brill 2021 (Library of Economic History, vol. 13)