Researching Theatre and Licensing records

Middlesex and Westminster Sessions: Music and Dancing Licences (MR/L/MD)

From 1752 to 1836 applications for music and dancing licences, if preserved, are to be found with the Middlesex and Westminster sessions papers. From 1837 they were kept as a separate series which survives for the years 1837, 1840, 1849-1860, 1877-1888. Petitions for or against the licence were sometimes filed with the application. The licences themselves survive for the years 1752, 1763, 1766, 1768-1781, 1823, 1844, 1880-1881. They give the name of the owner of the establishment, the address of the premises and terms of the licence. These have been catalogued in detail and our catalogues can be searched by name of premises or by the name of proprietor on the LMA Catalogue. Also included among the records of the Middlesex Sessions are printed lists of licences issued the previous year with manuscript notes of renewal which date from 1849 to 1888, justices’ and police reports, certificates of structural alterations to places of public entertainment, and plans accompanying the licence applications.

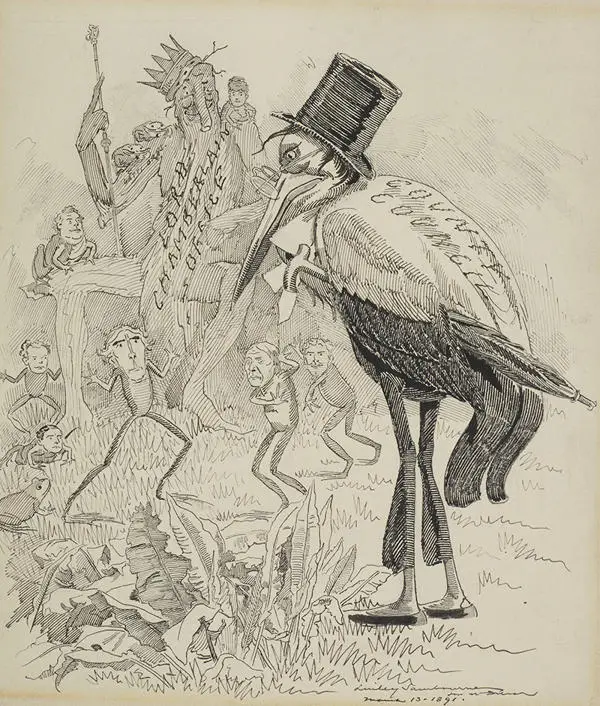

Lord Chamberlain’s Office

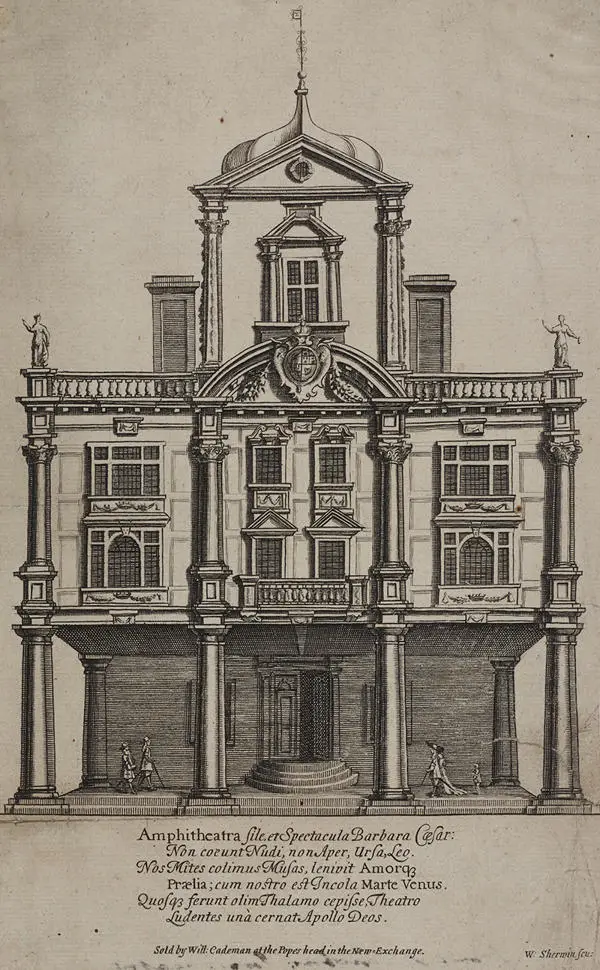

Prior to the Theatre Regulation Act of 1843 there were only two theatre companies which had the sole right to perform dramatic entertainment in London. Charles II reconstituted the theatre after the Restoration and granted royal patents to Sir William Davenant and Thomas Killigrew and their heirs which gave them the right to operate theatres in London as a monopoly.

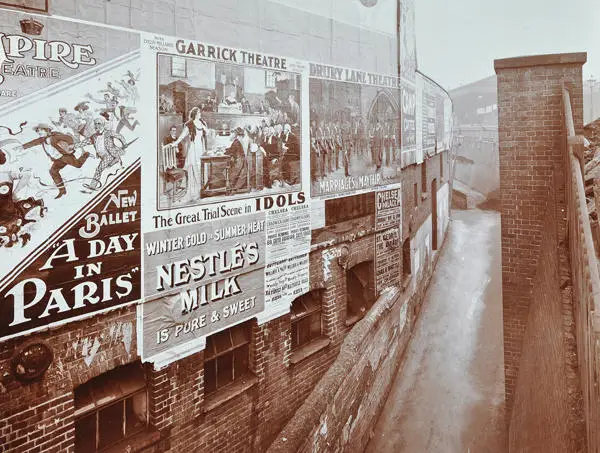

The Duke’s Company operated under Davenant’s patent and from 1660 performed at Dorset Garden Theatre. In 1682 the Duke’s Company amalgamated with the King’s Company and moved to the Drury Lane Theatre until 1732 when the Duke’s Company established itself at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden. The King’s Company operated under the Killigrew patent. From 1660 the company performed at Vere Street Theatre and from 1663 at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane.

The Little Theatre in the Haymarket offered the first serious competition to the two patent houses and had the capacity to survive without a patent or a licence. From 1735 to 1737 the theatre was managed by Henry Fielding. However, during this period a number of political satires were staged at the theatre which gave rise to the Licensing Act of 1737. This Act re-established the monopoly of the two patent theatres and introduced censorship of the stage by requiring the Lord Chamberlain’s approval of any play intended for performance. However, Samuel Foote obtained a royal patent for the Haymarket in 1766 which allowed it to open during the summer months for the duration of Foote’s life. After his death the theatre remained open on an annual licence.

The Theatre Regulation Act of 1843 brought an end to the patent monopoly and laid down a nationwide system of licensing. This allowed all theatres in the Cities of London and Westminster, and the boroughs of Finsbury, Marylebone, Tower Hamlets, Lambeth and Southwark to apply for a Lord Chamberlain’s licence which enabled them to perform drama. This Act therefore forced small saloon theatres to apply either for a magistrates’ music and dancing licence which permitted drinking but did not allow dramatic entertainment, or a Lord Chamberlain’s licence which permitted them to present drama but forbade drinking in the auditorium. As a result of this Act, theatres and music halls developed as distinctly separate entities.

The theatre files of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office dating from before 1902 are located at The National Archives, Ruskin Avenue, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU. The main classes of records are in LC7 which include warrants, registers of licences, inspection reports and plans of theatres from 1666 to 1901, and in LC1 which contains the correspondence of the Office of the Lord Chamberlain from 1710 to 1902; later records remain in the care of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office at St. James’s Palace. From 1737 until 1968 the Lord Chamberlain also had the power to censor all stage plays. The texts of the plays submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s Department from 1824 are now deposited in the British Library Manuscript Collections, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB.

A volume of papers relating to the licensing of theatres by the Lord Chamberlain can be found among the records of the London County Council Theatres and Music Halls Committee held at LMA (LCC/MIN/10927). This mainly relates to the contribution which the Council made to ensuring that theatres were safe from danger of fire because, from 1902, a Lord Chamberlain’s licence could only be obtained if the LCC had first provided written confirmation that theatres were adhering to fire regulations.

London County Council and the Empire Theatre Intervention

The case of the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square is the most famous instance of LCC intervention in the running of the music halls, although similar cases occurred at the Oxford and the Alhambra music halls. In 1894, one of the leading campaigners against vice in London, Mrs Ormiston Chant, attempted to oppose the Empire’s application for the renewal of its licence on the grounds that ‘the place at night is the habitual resort of prostitutes in pursuit of their traffic, and that portions of the entertainment are most objectionable, obnoxious, and against the best interests and moral well-being of the community at large’ (LCC/MIN/10803).

The LCC decided that it would only renew the Empire’s licence if a screen were put up between the promenade and the back row of the dress circle and the upper circle, to discourage soliciting in the promenade. The music hall was closed for a short time but when it was reopened the screen was pulled down immediately by a crowd of people. The Daily Telegraph gave great prominence to the proceedings of the licensing committee, and its letters page debating the issue of the Empire ran under the heading ‘Prudes on the Prowl’.

The inspectors’ reports and the proceedings before the Licensing Committee often provide revealing insights into the performances themselves as information on the lyrical content of songs and the behaviour of performers is cited as evidence against the renewal of a licence. In their reports the inspectors often target specific artists and their acts. In a report on the Oxford music hall an inspector notes that ‘Miss Marie Lloyd produces her characteristic effects, it seems to me, not so much by words and phrases that can be laid hold of and taken exception to as by her manners and actions - knowing nods, looks, smiles and winks full of suggestiveness...’ (LCC/MIN/10869).

The entertainment itself is also detailed in cases where a dispute arose over the definition of dramatic entertainment which had been prohibited in music halls by the Theatre Regulation Act of 1843. A hearing in 1889 following the application of the proprietor of the Canterbury music hall for a music and dancing licence details a debate over a performance of ‘The Stowaway’ showing how difficult it was to define and prohibit the performance of plays in music halls (LCC/MIN/10782).