Unforgotten Lives - exploring London's colonial links

The historic presence of people of colour in London can in many cases be traced back to British colonial activity. Although colonialism was not the sole reason for the people presented in Unforgotten Lives being in London during our period, it played a significant role. London was transformed by the wealth and power generated through enslavement and colonialism and its history cannot be separated from these colonial links.

By the end of the eighteenth-century London was a global city at the heart of a growing Empire. Many aspects of life in the capital were directly dependent on these colonial connections. Empire was not something which was happening overseas. It was being experienced and consumed on the streets of London. The diversity of its populations, the grandeur of its buildings, the wealth and power of its institutions and businesses, the richness of its cultures and the availability of daily commodities were intimately linked to empire. We need only look at the ritual of tea drinking in Britain, literally empire in a cup: the tea coming from China (and later India) and the sugar from the Caribbean.

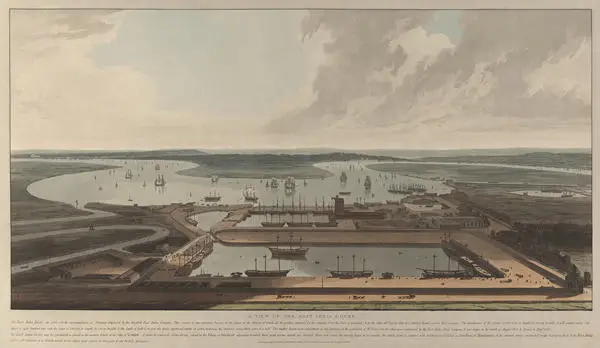

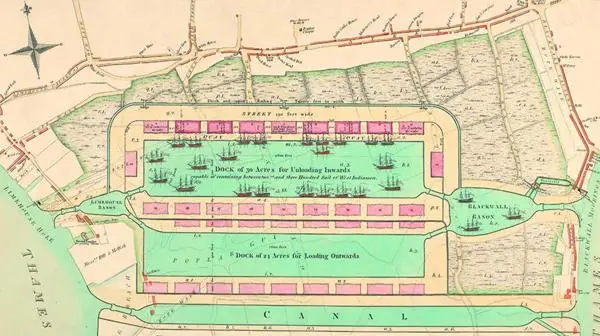

There is perhaps no clearer expression of these colonial links on London’s built environment than the development of the West India and East India Docks. Built at the turn of the nineteenth century, these huge projects incorporating enclosed docks, quays and warehouses were designed to increase the efficiency of processing these precious cargoes for the hundreds of ships which were passing through London.

The building of the West India Docks was one of the most ambitious public works projects of its kind. Demanded by West India merchants in 1790s, the system was designed to reduce the losses in revenue caused by the congestion, delays and pilfering within the Pool of London, the stretch of the Thames adjacent to the City of London. The closed dock system revolutionised the process when it opened in 1802. The East India Company took note and introduced similar structures to its operations in Blackwall, with the East India Docks opening in 1806.

In 1823, a Customs officer reported that “Since the West India Docks were opened for business, the system, both with regard to the revenue and the West India Dock Company, has been brought to a state of perfection scarcely to be surpassed”.