Elyssa Rider

Elyssa is a queer Japanese and British illustrator and comic artist working in pencil, traditional paint and digital paint. She uses humour in her comics to release grief, rage, and shame through raw depictions of the encounters she experiences in life.

Through making art about things that are usually kept private, Elyssa gives permission to the viewer to join her in shamelessness. In her paintings, Elyssa uses bold, clean, vibrant colour to depict voluptuous queer scenes. She depicts romantic global majority couples in a way that is free from a fetishising gaze.

Artist's vision

Elyssa is interested in responding to the Unforgotten Lives exhibition with dignified, respectful and sensitive illustrations to bring to life how these individuals may have looked. She is particularly interested in depicting the love captured in the archives, as much of her work focuses on romance and sensuality, and she wants to create work which brings recognition to how people at the time were willing to go against the grain in the name of love and connection.

Elyssa hopes her exhibition response will help to fill the silences of who these people were, whilst avoiding harmful stereotypes and caricatures. Her interest is in depicting people of colour in a celebratory and careful way, whether they are doing something extraordinary, or simply existing doing regular everyday things.

“I aim to make people feel seen, particularly queer people of colour, whose stories are often overlooked or omitted entirely.”

The Artwork

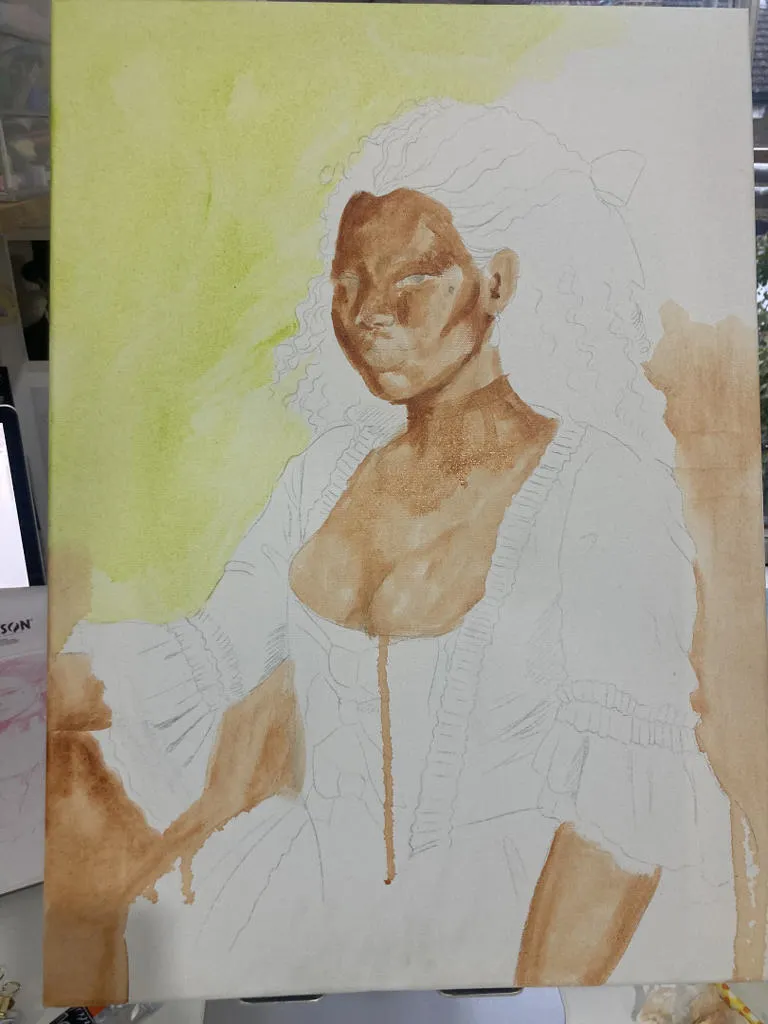

Interpretation of Ann Duck

This painting shows an imagined interpretation of what Ann Duck may have looked like. The intention was to show Duck as confident, well put-together, and sure of herself. This challenges the viewer to see her as more than the records we have, which only depict her criminal charges. She is shown in a more vibrant version of the colours that were likely available in the day.

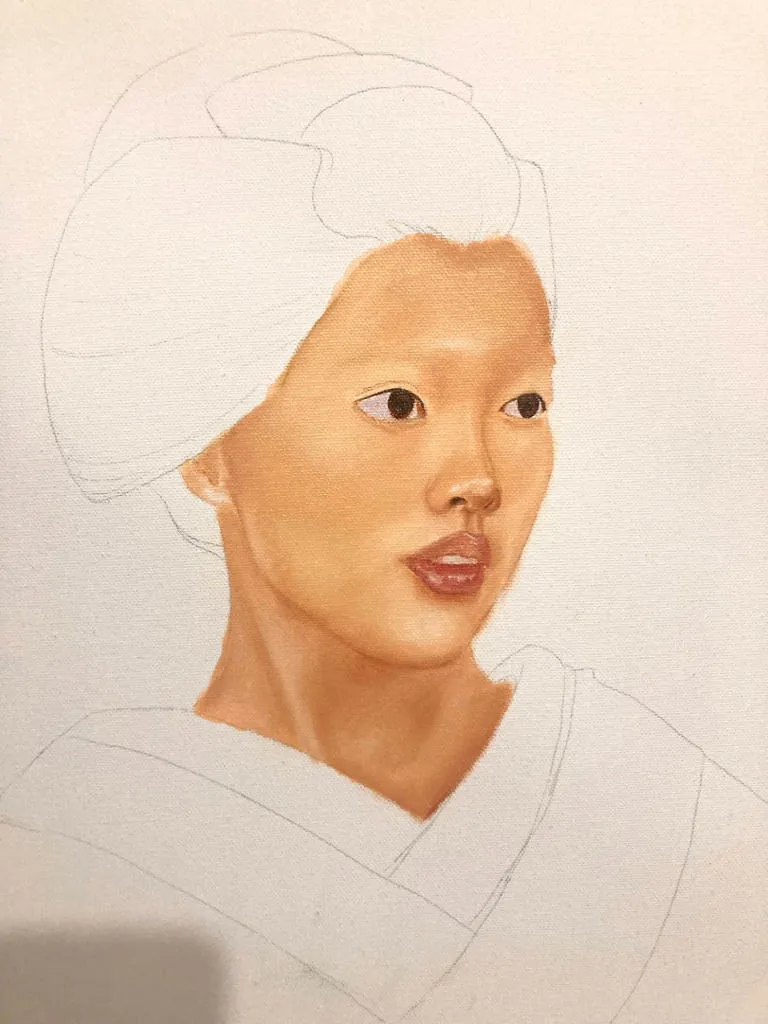

This painting shows an imagined interpretation of what a Japanese merchant may have looked like visiting London in 1600, before Japan closed its borders in 1603. She is intentionally shown looking up and speaking as a rejection of the stereotype of Asian women being timid and submissive. Her kimono bears a design of mountains and wisteria.

Elyssa Rider in Conversation

In her own words, read about what drew Elyssa to the Art at the Archive project and more about the work that they are creating

I feel particularly called to create this work, as someone who feels very firmly rooted in London, and yet is constantly asked, ‘no, where are you Really from?’ My desire is to engage with the archive as a form of validation and vindication, and show how we have always been here, and we belong here just as much as anyone else.

Also my Japanese ancestors moved to London briefly to study during the time period covered by the Unforgotten Lives Exhibition and so I was really curious to see if there might be any records of any other Japanese people here during that time.

This is actually my first time visiting an archive in person, as usually the way I engage is through archival accounts on Instagram. The accounts I follow post photos and images from Japanese cultural and fashion history. Two particular favourites are @ko_archives and @fruits_magazine_archives and I enjoy them as a way of engaging with my Japanese heritage as a mixed race diasporic person.

For me, archives feel like ‘filling in the blanks’ and almost borrowing someone else’s memories and history as a way of enriching my own. Having never lived in Japan longer than three months, it’s easy for me to feel disconnected, but archives offer me a sense of access and belonging.

From my understanding she was a young woman living in London who we suspect was working as a sex worker and had associations with the ‘Black Boy Alley Gang’. She was frequently tried for ‘alleged robbery’ of her clients. This sort of narrative doesn’t feel misplaced in a contemporary setting which made her feel so familiar. She was a hustler. “Expert a mistress in all manner of wickedness, as Satan himself could make her.” I mean come on. What a write up! Let’s just say I support women’s rights and women’s wrongs… I was really drawn to the story of Ann Duck as a fellow biracial person, and as someone grafting to try and keep afloat in London.

My hope is that by putting a face to a name, in a sense, my art will help visitors to the exhibition feel a stronger sense of empathy with people recorded in the archives.

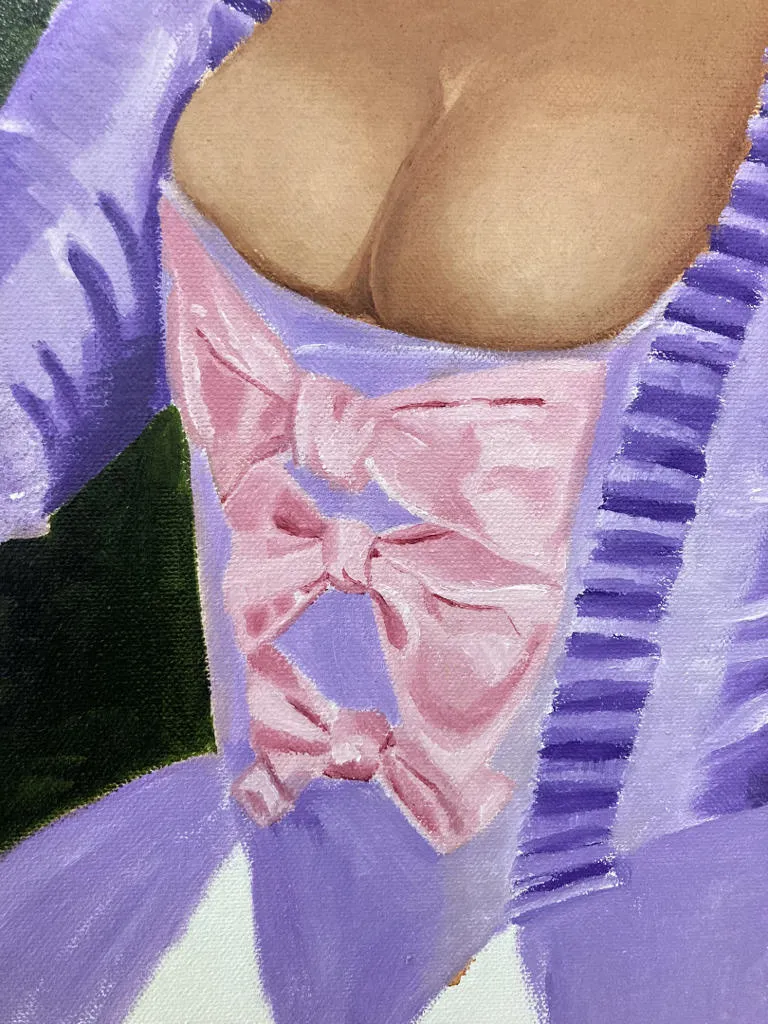

I wanted the art to be in keeping with the traditional style of the time to prevent it from jarring against the rest of the exhibition, whilst leaving some parts of myself in the work so that it is recognisable as mine. For example, I wanted my representations to include colour schemes like lilac and baby pink, and motifs that I use in the rest of my art, even though they are perhaps not strictly historically accurate.

I was really concerned about representing a Black mixed raced woman and East Asian woman in a way that felt truthful, dignified, and respectful as well as historically accurate. One challenge I experience was finding any sources about how Black women did their hair during this period. And particularly, in the case of Ann Duck, where we can presume that she worked in sex work and had some money to spend on her appearance, she may have wanted to dress and style herself in a way that would attract clients. So, I've been trying to research what kind of accessories she might have used, and what kind of clothing styles she would have worn.

I also am conscious about wanting to avoid falling into White supremacist depictions of Black mixed-race women and particularly to avoid colourist and texturist ideals of beauty whilst also acknowledging that Ann Duck was part white. I am intentionally going to depict her hair as being black and her eyes are being dark brown even though I have no evidence of this, as a result.

The archives I’m looking at can be a little scant in terms of detail and the problem is that racial descriptors and categories at the time were used almost randomly and inconsistent with their current usage. This means I can’t be certain of who exactly is being recorded, and how they might self-describe if they were alive today. Plus lots of people chose or were forced to change their names to white Christian ones, so even the names can’t always help me. There’s a large degree of guesswork happening.

When searching for helpful reference images, they needed to not only be women from this period, but Black women from this period, and not only Black women from this period but Black female sex workers from this period. Unfortunately, there was barely anything I could work with as a result. This was the same for looking at reference images of East Asian women in London at the time. One of the really grim side effects of looking through the archives is that often when East Asian people crop up, they, we, get described using horrendous terms and slurs and reading that perception is deeply painful and angering.

It’s been exciting! I feel like I’ve been given an exclusive look behind-the-scenes at Narnia. I’ve never worked on a historically based piece before and I’ve relished the opportunity to research alongside the team and be guided by them around how to access the archives for my needs.

My hope is that my work will add to the nuance of the archival space by disrupting the impression that we are given of Ann Duck by the official records; that she was a criminal and nothing more. I wanted to show her as someone who felt real and had a future and potential, and who was robbed of this by the state. I also wanted to show how young she was to remind the viewer how much the state robbed from her.

I think in the overall exhibition there were not that many images of women and I wanted to help to address that. I hope that the work will engage people’s empathy and particularly hope that people with Black mixed heritage will feel honoured and respected by the work as my attempt to contravene the caricature art frequently made at the time.

My Instagram is @elyssa_rider and is where I post my work most frequently and I’m currently working on my website so watch this space!