The White Horse, Poplar High Street

Stories of ‘Female Husbands’, cross-dressing and ‘women soldiers’ were very popular in the press during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. These tales intrigued all levels of society, filling popular ballads and chapbooks (cheaply produced street literature) to the comedies and tragedies of aristocratic literature. While these have been told as fantastical accounts of deceit and betrayal, they reveal a history of real people who defied gender expectations and the spaces they could express those identities.

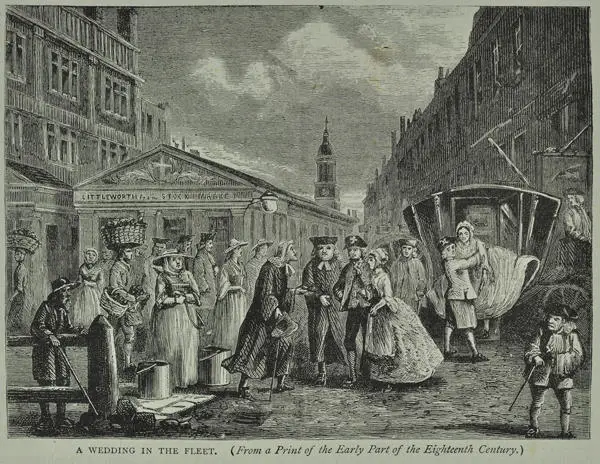

Mr and Mrs How were one couple that fascinated for centuries, with even Bram Stoker writing about this 18th century pair in 1910. As a couple they ran a succession of taverns at Epping, then Limehouse, before settling as the landlords of the White Horse on Poplar High Street in 1745. Like many others during this period, James How and Mary Snapes married outside Fleet Prison in December 1732. But how their relationship began is far more unusual.

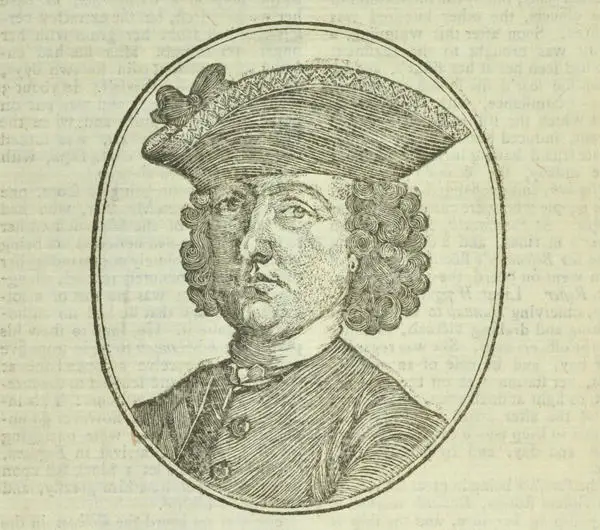

The way the Hows’ story historical been told involves a convenient anecdote that Mary and James were so disappointed by unsuccessful love affairs with men that they decided to live together instead. They devised a plan, but knowing they were living as two women, one should put on man’s apparel so they could live safely as man and wife. The decision about who should be the husband was allegedly decided by chance – the toss up of a halfpenny. Although framed like this in the press in a non-threatening heteronormative and cisnormative way, which reflected dominant ideas of the time, it is entirely probable that the two were lovers and James – while assigned female at birth – chose to trans gender and live as a man.

Apart from a disagreement with a young gentleman while in Epping, which left James with an injured hand and 500 pounds in damages, Mr and Mrs How lived seemingly peaceful and successful lives. James’ family was poor but managed to work their way up to become a prosperous and respected business owner, enabled in part by their transition. The Hows’ managed to save money, buying more properties. While private people, never known to host dinner parties or employ servants, they remained respected and integrated in their community. James served all the parish offices in Poplar, except constable and churchwarden.

Living outside of conventional gender norms meant life was always on the brink of instability. When a woman named Mrs Bentley recognised James from childhood, she threatened to ‘out’ them as female. James agreed to pay ten pounds to prevent Mrs Bentley destroying their happy, quiet life. Bentley seems to have left James alone for over 15 years, before returning to demand money two more times. On the following visit Bentley sent two men impersonating police officers, who threatened to arrest James for false crimes.

After a series of increasing distressing threats and physical abuse, James knew the only way to clear their name of the false crimes was to remove the power of the extortionist and publicly address the issues of their gender. Left with no other choice, James knew the only way to save themselves – quite possibly their life, freedom, property and reputation – was to speak of their past and to reassociate with the category of woman.

When the legal hearing against Mrs. Bentley and her co-conspirators was held, James arrived dressed in women’s clothing and used their deadname, Mary East. It was reported that “the alteration of [James’] dress from that of a man to that of a woman appeared so great, that together with [James’] awkward behaviour in [their] new assumed habit, caused great diversion to all...”

The exposure of James’ difference could have devastated them. James handed over a total of 25 pounds in exchange for keeping their secret for fifteen years: a small price to pay for the joy and acceptance they found. Financially, this was equivalent to a penalty of nearly two pounds a year, almost double the amount James paid in taxes during the 1760s. This is an early example of the ways that transgender, gender non-conforming and people with same-sex desires throughout history have been casually financially punished for their choices.

After the hearing James presented publicly as a woman for the rest of their life, likely no longer able to live as their chosen masculine identity. For James’ male contemporaries, playing with gender, including people assigned male at birth presenting as women, was widely known. But the same agency and fluidity was not allowed for those assigned female who embraced masculine traits or claimed a male identity. James How died in June 1780, leaving money to relatives, friends, and the poor of Poplar, and were buried under the name Mary East. All that remains of the White Horse on Poplar High Street is the 18th century sign, perhaps a better reminder of James’ life, being the sign that Mr and Mrs How saw every day.